When you get a new organ, your body doesn’t know it’s supposed to accept it. It sees the kidney, heart, or liver as an invader-and it will try to destroy it. That’s where immunosuppressants come in. These drugs calm down your immune system so your body doesn’t reject the transplant. But they don’t just stop rejection. They also open the door to serious risks: infections, cancers, kidney damage, and more. For transplant patients, taking these medications isn’t optional. It’s a daily balancing act between staying alive and staying healthy.

How Immunosuppressants Work

Immunosuppressants don’t work the same way. Each class targets a different part of the immune system. The most common types are calcineurin inhibitors (like tacrolimus and cyclosporine), antiproliferatives (like mycophenolate), corticosteroids (like prednisone), and mTOR inhibitors (like sirolimus and everolimus). Most patients take a mix of two or three of these drugs right after transplant. This combo approach gives stronger protection against rejection while lowering the dose of each drug, which helps reduce side effects.Tacrolimus, for example, blocks signals that tell T-cells to attack. Mycophenolate stops immune cells from multiplying. Corticosteroids shut down multiple parts of the immune response at once. And mTOR inhibitors slow down cell growth, which helps prevent rejection-but also slows healing. Each drug has its own risks, and doctors pick combinations based on the organ you got, your age, your other health problems, and how your body responds.

The Big Risks: Infections and Cancer

Because these drugs suppress your immune system, you’re more vulnerable to infections. That’s why everyone gets antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals for the first few months after transplant. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is one of the most common threats-especially if you got an organ from someone who had the virus and you didn’t. Without preventive treatment, up to 70% of these patients get sick.Long-term, the bigger worry is cancer. Immunosuppressants increase your risk of skin cancer, lymphoma, and other cancers by 2 to 4 times compared to the general population. The more drugs you take and the longer you take them, the higher the risk. That’s why transplant patients are urged to get regular skin checks, avoid sun exposure, and report any new lumps or unexplained weight loss right away. Some drugs, like mTOR inhibitors, are even used in low doses to help lower cancer risk in certain patients-because they’re less likely to promote tumor growth than calcineurin inhibitors.

Organ-Specific Risks and Timing

Not all transplants are the same. The heart and lungs are the most aggressive organs when it comes to rejection-they can start rejecting within days. Kidneys take weeks to months. Livers are the most forgiving; rejection can take years to develop. That affects how doctors adjust your meds.For example, everolimus has a black box warning for kidney thrombosis in the first 30 days after transplant. That means it’s rarely used early on in kidney recipients. Sirolimus, another mTOR inhibitor, is outright avoided in liver and lung transplant patients because it’s linked to higher death rates and graft failure in those groups. Meanwhile, corticosteroids are often slowly reduced or stopped after the first year because their long-term side effects-like bone thinning, diabetes, and weight gain-outweigh their benefits for many patients.

Side Effects You Can’t Ignore

Each class of drug has its own signature problems:- Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, cyclosporine): Kidney damage in 30-50% of long-term users, high blood pressure, tremors, and gum overgrowth.

- Corticosteroids (prednisone): Weight gain, diabetes (10-40% of patients), osteoporosis (30-50%), cataracts, and mood swings.

- Mycophenolate: Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting (30-50% of users), and low white blood cell counts that raise infection risk.

- mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus, everolimus): Delayed wound healing (20-30%), high cholesterol (30-50%), mouth sores, and rare but deadly lung inflammation (pneumonitis in 1-5%).

These aren’t rare side effects. They’re common. And they’re not always obvious at first. A patient might think their fatigue is just from surgery, but it could be low blood counts from mycophenolate. A rash might be mistaken for allergies, but it could be early signs of skin cancer. That’s why regular blood tests, kidney function checks, and cancer screenings aren’t optional-they’re life-saving.

Adherence: The Most Critical Factor

You can have the perfect drug combo, the best doctor, and the cleanest lifestyle-but if you miss a dose, you’re at risk. Studies show that more than half of kidney transplant patients don’t take their meds exactly as prescribed. Some forget. Some skip doses because of side effects. Some can’t afford them. Others think they’re fine now, so they cut back.That’s dangerous. Missing even one dose can trigger rejection. A 2023 review found that patients who skip doses are 2.8 times more likely to have late rejection. Those who delay doses are 3.5 times more likely to develop heart disease in the transplanted organ. And once rejection starts, it’s harder to reverse. The damage can be permanent.

Simple fixes help. Switching to once-daily versions of tacrolimus. Using pill organizers. Setting phone alarms. Using apps that send reminders. One study showed that these small changes boosted adherence by 15-25%. If you’re struggling to keep up, talk to your pharmacist. There are programs that help with costs. There are nurses who specialize in transplant care. You’re not alone.

What Happens When You Stop?

Some patients wonder: Can I stop these drugs someday? The short answer is: rarely. For most, immunosuppressants are lifelong. There are rare cases where patients develop “operational tolerance”-their body accepts the organ without drugs. But this happens in less than 5% of cases, mostly in liver transplants, and only after years of careful monitoring.Stopping on your own? That’s a disaster. Abruptly stopping immunosuppressants can cause rapid organ failure. The symptoms vary by organ: less urine output (kidney), belly pain and swelling (liver), cough and trouble breathing (lungs), chest pain or heart failure (heart). If your transplant fails, you may need to go back on dialysis, get another transplant, or face life-threatening complications. Never stop your meds without your doctor’s direction.

The Future: Smarter, Safer Medication

Doctors aren’t sitting still. Newer strategies are emerging. Some centers now use blood tests to measure immune activity and adjust doses based on your personal risk-not just a one-size-fits-all plan. Low-risk patients might get lower doses of calcineurin inhibitors, reducing kidney damage without increasing rejection. Others are testing drugs that train the immune system to accept the organ without full suppression.For now, the goal is balance. Enough drug to stop rejection. Not so much that you get sick or die from side effects. It’s not perfect. Transplant recipients still live shorter lives than the general population. But thanks to better drugs and smarter care, many are living 20, 30, even 40 years after their transplant. That’s a miracle. And it’s all because of these pills.

What You Can Do Today

- Take every pill, at the exact time, every day. No exceptions.

- Keep all blood tests and clinic visits-even if you feel fine.

- Wash your hands often. Wear a mask in crowded places. Avoid sick people.

- Use sunscreen daily. Check your skin weekly for new moles or sores.

- Ask for help if you can’t afford your meds. Many hospitals have financial aid programs.

- Use reminders. Set alarms. Use a pill box. Tell a family member to check on you.

These aren’t suggestions. They’re survival tools. Your new organ is a gift. But it needs daily care. And the only way to protect it is by taking your meds-exactly as prescribed.

Can I stop taking immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Feeling fine doesn’t mean your immune system isn’t slowly attacking your transplant. Stopping these drugs-even for a few days-can trigger sudden, irreversible rejection. Most transplant patients need to take immunosuppressants for life. Only a tiny fraction of patients (under 5%) ever reach a point where doctors consider reducing or stopping them, and even then, it’s done under strict monitoring.

Which immunosuppressant has the least kidney damage?

mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus and everolimus are less likely to cause kidney damage than calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus and cyclosporine. While CNIs damage kidneys in 30-50% of long-term users, mTOR inhibitors cause kidney problems in only 10-20%. But they come with other risks, like delayed healing and lung inflammation. Doctors may switch patients from CNIs to mTOR inhibitors years after transplant to protect kidney function, especially if the patient is stable and low-risk.

Why do I need blood tests every month?

Your blood levels of immunosuppressants must stay in a narrow range. Too low, and your body rejects the organ. Too high, and you get toxic side effects like kidney damage, tremors, or high blood pressure. Blood tests tell your doctor if your dose needs adjusting. They also check for signs of infection, low blood counts, or liver/kidney problems. Skipping these tests is like driving blindfolded-you might be fine today, but you’re at serious risk tomorrow.

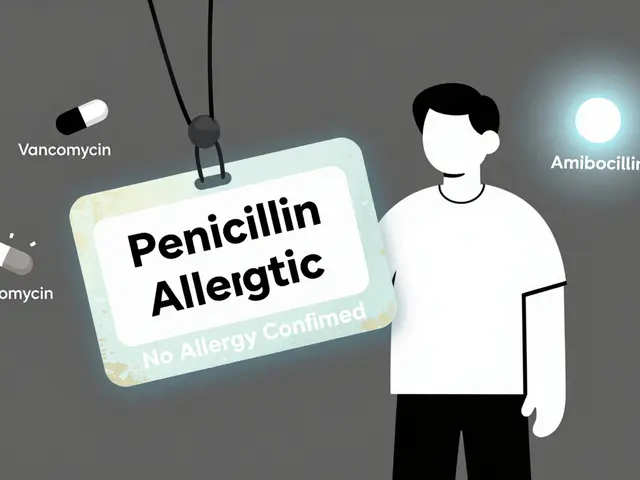

Are generic versions of immunosuppressants safe?

Generally, no. Even though generics are chemically similar, small differences in how they’re absorbed can cause big changes in your blood levels. For drugs like tacrolimus and cyclosporine, even a 10% change in concentration can lead to rejection or toxicity. Most transplant centers require you to stay on the same brand or generic version once you start. If you switch, your doctor will need to monitor your levels more closely and adjust your dose.

Can immunosuppressants cause weight gain?

Yes, especially corticosteroids like prednisone. These drugs increase appetite, cause fluid retention, and change how your body stores fat-often around the face, belly, and back. Weight gain is one of the most common complaints among transplant patients. Doctors often reduce or stop steroids after the first year to help with this. Eating a low-salt, low-sugar diet and staying active can help manage it. Never stop steroids on your own, though-doing so can cause dangerous drops in blood pressure.

What should I do if I miss a dose?

If you miss one dose, take it as soon as you remember-if it’s within a few hours of your usual time. If it’s been longer, skip the missed dose and take your next one at the regular time. Never double up. Call your transplant team right away. They may want to check your drug levels or schedule an extra visit. Missing doses increases rejection risk, so it’s important to report it-even if you think it’s no big deal.

Do immunosuppressants interact with other medications?

Yes, badly. Common drugs like antibiotics, antifungals, seizure meds, and even some herbal supplements (like St. John’s Wort) can change how your immunosuppressants work. Grapefruit juice can make tacrolimus levels dangerously high. Over-the-counter painkillers like ibuprofen can hurt your kidneys when combined with these drugs. Always check with your transplant pharmacist before taking anything new-even vitamins or cold medicine.

How do I know if my transplant is being rejected?

Early rejection often has no symptoms. That’s why blood tests and biopsies are so important. But if rejection does become severe, symptoms depend on the organ: kidney (less urine, swelling, high blood pressure), liver (yellow skin, dark urine, belly pain), heart (shortness of breath, fatigue, swelling in legs), lungs (cough, fever, trouble breathing). If you notice any of these, contact your transplant team immediately. Early treatment can reverse rejection.

13 Comments

Take every pill. Every. Single. One. I know it’s a grind, but this isn’t just medicine-it’s your new heartbeat. Miss one, and you’re playing Russian roulette with a gift someone else died to give you.

i just started my second year post-kidney and honestly the worst part isnt the pills its the fear of forgetting. i use a pill box with alarms and my mom checks on me. its kinda sweet. also sunscreen. always sunscreen.

you’re all being too nice. this is just a slow death sentence with a side of steroids.

lol so we’re supposed to believe ‘operational tolerance’ is real but also ‘never stop meds’? sounds like the medical industrial complex got a nice subscription model going. 🤡

oh please. you think skipping a dose is dangerous? try living with a face full of steroid moon and trembling hands while your kidneys scream. this isn’t medicine-it’s punishment dressed in white coats.

One must contemplate the existential paradox of the immunosuppressed: we are, by pharmacological decree, both alien and assimilated-our bodies are battlegrounds of metaphysical betrayal, where the organ is both savior and stranger. The pill, then, becomes the sacrament of a secular covenant: a daily atonement for the sin of survival.

Yet, in this ritual, we are not merely patients-we are pilgrims in the cathedral of modern medicine, bowing before the altar of tacrolimus, offering our lymphocytes as burnt sacrifices upon the pyre of immune orthodoxy.

Is this not the ultimate irony? To live, we must become less alive-our immune systems, once fierce and proud, now neutered, obedient, hollow. We are not healed. We are pacified.

And yet-there is beauty in this surrender. In the quiet discipline of the pillbox, the alarm, the blood draw at dawn-we reclaim agency in a world that reduces us to biomarkers.

Perhaps, then, the true miracle is not the organ-but the will that rises each morning to swallow the poison that keeps it beating.

And still… we wonder: if the body remembers the wound, does the soul remember the gift?

It is not the drugs that save us. It is the silence we keep between doses. The discipline. The grief. The love.

And yes-sunscreen. Always sunscreen.

But let us not mistake compliance for cure. We are not cured. We are deferred. And every lab result is a verdict whispered in Latin.

So I ask you: when you take your pill, do you thank the donor? Or do you curse the disease that stole their life to give you yours?

And if you could choose: would you rather be whole-or merely, mercifully, alive?

my brother got a liver transplant 12 years ago. he stopped his meds for three days once because he was tired of the side effects. ended up in ICU. now he takes them with a smoothie every morning and says it’s his ‘quiet time.’

don’t wait for the crisis to start caring. just do it. every day.

While the clinical data presented is comprehensive, it is worth noting that adherence metrics vary significantly across socioeconomic strata. Access to pharmacy support, transportation to clinics, and mental health resources remain critical unaddressed variables in long-term transplant outcomes.

what if i just… didn’t take them? 😏

bro i missed a dose last week and my doctor didn’t even yell. just said ‘next time call us’ and gave me a free pill organizer. its not perfect but you got people who care. dont give up.

you’re not broken. you’re not weak. you’re not failing. you’re just doing something incredibly hard. every time you take that pill, you’re choosing life. and that’s enough.

in my country, we call transplant patients ‘miracle survivors.’ but you know what? the real miracle isn’t the organ. it’s the person who shows up every day-even when they’re tired, scared, broke, or angry. you’re the miracle. keep going.

yo i been there. lost my spleen to cancer, got a liver, now i got 3 pills at 7am, 2 at 7pm, and a bottle of sunscreen bigger than my dog. i cry sometimes. i curse sometimes. but i take ‘em. because i ain’t done living yet. 🙏🔥