What Is IgA Nephropathy?

IgA Nephropathy is an autoimmune kidney disease where immune complexes made of immunoglobulin A (IgA) build up in the filtering units of the kidneys, called glomeruli. This triggers inflammation that slowly damages kidney tissue over time. Also known as Berger’s disease, it was first identified in 1968 and is now the most common cause of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide. In Western countries, it accounts for 25-40% of cases; in parts of Asia, that number jumps to nearly 50%. It often shows up in teenagers and young adults, sometimes after a cold or sore throat, with visible blood in the urine. But many people don’t notice symptoms until routine blood or urine tests reveal protein or microscopic blood in the urine.

How Bad Is the Prognosis?

The outlook for IgA Nephropathy varies widely. About half of people with persistent proteinuria will develop kidney failure within 10 to 20 years after diagnosis. That’s not a guarantee - it’s a risk. Some people live for decades with stable kidney function. Others decline faster, especially if they have high blood pressure, heavy protein loss in urine, or scarring seen on kidney biopsy. The KDIGO 2025 guidelines now stress that the biggest predictor of long-term damage isn’t just how much protein is in the urine - it’s how long it stays high. Even people with proteinuria between 0.44 and 0.88 grams per gram of creatinine (a common lab measurement) still had a 30% chance of reaching kidney failure within 10 years. That’s why the new target isn’t under 1 gram per day anymore - it’s under 0.5 grams per day. But here’s the catch: no study has proven that pushing proteinuria this low actually improves outcomes. Doctors are still figuring out how far to go.

What’s Changed in Treatment? The KDIGO 2025 Shift

Before 2025, the standard was to start with blood pressure meds - usually ACE inhibitors or ARBs (RASi) - and wait three months to see if proteinuria dropped. Only then would doctors consider immunosuppressants. That delay meant the immune system kept attacking the kidneys while patients waited. The KDIGO 2025 guidelines flipped this model. Now, if you’re at high risk - meaning proteinuria above 0.75 grams per day plus other risk factors like high blood pressure or biopsy damage - you start both anti-proteinuric therapy and immunosuppression at the same time. This isn’t just a tweak. It’s a complete rethink. Studies now show that waiting allows irreversible damage to accumulate. The goal is to stop the disease in its tracks early, not react after it’s already causing harm.

Current Therapies: What’s Actually Used

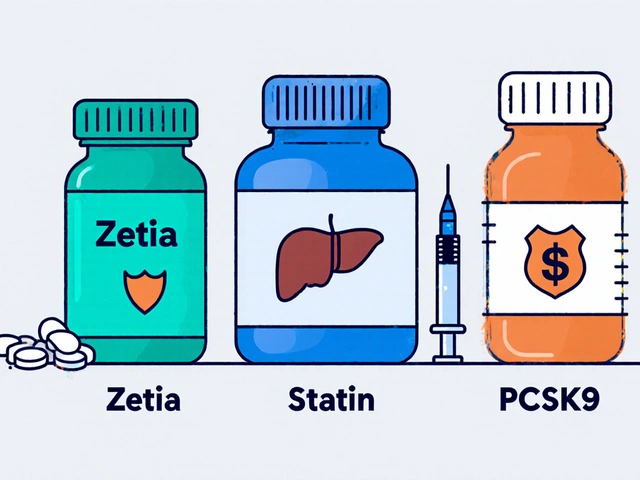

There are now several treatment options, each with different roles:

- RAS inhibitors (like losartan or lisinopril): These are still the foundation. They lower blood pressure and reduce protein leakage. Almost everyone gets these.

- SGLT2 inhibitors (like dapagliflozin or empagliflozin): Originally for diabetes, these drugs also reduce kidney stress and proteinuria in non-diabetic patients. They’re now routinely added to RASi for high-risk cases.

- Nefecon: This is the first drug approved specifically for IgA Nephropathy (FDA approved December 2023). It’s a targeted-release steroid that acts in the gut to reduce production of abnormal IgA. It’s not a systemic steroid - so fewer side effects like weight gain or mood swings. Patients in trials saw proteinuria drop by 40-50% in a year.

- Systemic corticosteroids (like prednisone): Still used, especially where Nefecon isn’t available. But they come with risks: bone loss, diabetes, infections. Doctors now use lower doses for shorter periods, and only in patients who can tolerate them.

- Sparsentan (a DEARA): Approved by the EMA in 2024, this drug blocks two pathways that cause kidney damage. Early results show it cuts proteinuria more than RASi alone. It’s not yet FDA-approved for IgAN but is being fast-tracked.

Regional differences matter. In Japan, tonsillectomy is common - up to 45% of patients get it, based on studies showing fewer flare-ups after removal. In China, mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine are frequently used. But these treatments don’t have strong evidence in Western populations. That’s why global guidelines avoid recommending them universally.

What About Side Effects and Quality of Life?

Patients aren’t just numbers. Many report feeling overwhelmed managing multiple pills. One 16-year-old on Reddit said, “I have four different meds with different times to take them. It’s exhausting.” Nefecon is easier to tolerate than steroids - 72% of patients in a 2025 survey said they had fewer side effects. But cost is a huge barrier. Nefecon costs $125,000 a year in the U.S. Many insurance companies deny it at first. Patients often need to appeal multiple times. In low- and middle-income countries, access to even basic RAS inhibitors is limited. Only 22% of patients there get guideline-recommended care, compared to 85% in wealthy nations. The goal isn’t just to save kidneys - it’s to save quality of life without breaking the patient or the system.

How Is Progress Measured?

Doctors track three things closely:

- Proteinuria: Measured in grams per day or grams per gram of creatinine. The target is now <0.5 g/day. Monthly checks are recommended for the first three months, then quarterly.

- Blood pressure: Must stay below 120/75 mmHg. High pressure speeds up kidney damage.

- eGFR: This measures how well kidneys filter waste. A steady drop over time signals progression.

Biopsy results from the Oxford MEST-C score help predict risk - especially if there’s scarring (T score) or swelling in the glomeruli (E score). But there’s no blood test yet that can tell you which treatment will work best for you. That’s the next frontier.

What’s Coming Next?

The future of IgA Nephropathy is personalized. Right now, treatment is based on clinical signs: protein levels, blood pressure, biopsy results. But researchers are hunting for biomarkers - molecules in blood or urine that show exactly which pathway is driving the disease in each person. Are you overproducing IgA? Is your complement system overactive? Is your gut microbiome triggering bad immune responses? Trials like TARGET-IgAN (due in 2027) are testing whether matching drugs to these biomarkers improves outcomes. If it works, you won’t get “the standard treatment.” You’ll get the treatment your body needs. Companies are already developing drugs that block APRIL (a protein involved in IgA production) and complement inhibitors. These could be game-changers.

Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

IgA Nephropathy isn’t rare. It affects 2.5 to 3.5 people per 100,000 each year - and more in Asia. The global market for treatments is expected to hit $2.1 billion by 2030. But behind the numbers are real people. A mother in Ohio spent six months fighting her insurance to get Nefecon approved. A college student in India can’t afford even generic RAS inhibitors. The new guidelines are scientifically strong, but they’re only as good as the systems that deliver them. Without access, equity, and affordability, even the best science won’t help.

What Should You Do If You’re Diagnosed?

If you’ve been diagnosed:

- Ask for a full risk assessment using the KDIGO calculator - proteinuria, blood pressure, eGFR, and biopsy score.

- Don’t wait. If you’re high risk, push for simultaneous therapy - RASi + SGLT2i + Nefecon or steroids - right away.

- Track your numbers. Keep a log of urine protein, blood pressure, and how you feel.

- Ask about cost support programs. Calliditas (maker of Nefecon) and other companies offer patient assistance.

- Join a support group. The IgA Nephropathy Support Group on Facebook has over 8,500 members sharing real experiences.

There’s no cure yet. But the tools to slow or stop progression have never been better. The key is acting early, staying informed, and demanding care that matches your needs - not just the textbook.

Can IgA Nephropathy be cured?

No, there is no cure for IgA Nephropathy yet. But the goal of modern treatment is to stop or significantly slow progression to kidney failure. With early, aggressive therapy - especially using Nefecon, SGLT2 inhibitors, and RAS blockers - many patients can maintain stable kidney function for decades. Some even reach near-normal proteinuria levels and avoid dialysis entirely.

How long does it take for Nefecon to work?

Most patients see a drop in proteinuria within 3 to 6 months of starting Nefecon. The full effect usually takes about a year. Clinical trials showed that 40-50% of patients achieved proteinuria under 0.5 g/day after 12 months. It’s not an instant fix - but it’s more effective and better tolerated than long-term steroids.

Is a kidney biopsy always necessary?

Not always, but it’s strongly recommended for anyone with persistent proteinuria above 0.5 g/day or declining kidney function. The biopsy confirms IgA Nephropathy and gives the MEST-C score, which helps predict how fast the disease might progress. This score directly influences treatment decisions - like whether to start immunosuppression right away.

Can I stop my meds if my proteinuria improves?

Don’t stop without talking to your nephrologist. Even if proteinuria drops below 0.5 g/day, stopping treatment too soon can lead to rebound damage. Most patients need to stay on RAS inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors long-term. Nefecon is usually taken for 9 months, then stopped. But maintenance therapy with blood pressure and kidney-protective drugs continues indefinitely.

What lifestyle changes help with IgA Nephropathy?

Diet and habits matter. Reduce salt intake to help control blood pressure. Avoid NSAIDs like ibuprofen - they can worsen kidney damage. Quit smoking. Maintain a healthy weight. Stay active. Limit processed foods and excess protein. These don’t replace meds, but they support them. Studies show patients who combine good lifestyle habits with medication have slower disease progression.

Final Thoughts: Hope With Realism

The last five years have changed everything for IgA Nephropathy. What was once a slow, passive disease with few options is now a treatable condition with targeted drugs, clear goals, and better outcomes. But progress isn’t automatic. It requires early diagnosis, access to new therapies, and patients who know their rights and options. The next decade will bring even more - biomarker-guided treatment, new drugs, and global efforts to close the care gap. The promise is real: to keep kidneys working, not just for years, but for a lifetime.