Learn how the immune system can trigger or worsen central diabetes insipidus, how to spot the link, diagnose it with labs and MRI, and treat both hormone loss and inflammation.

Read MoreVasopressin – The Body’s Water‑Balancing Hormone

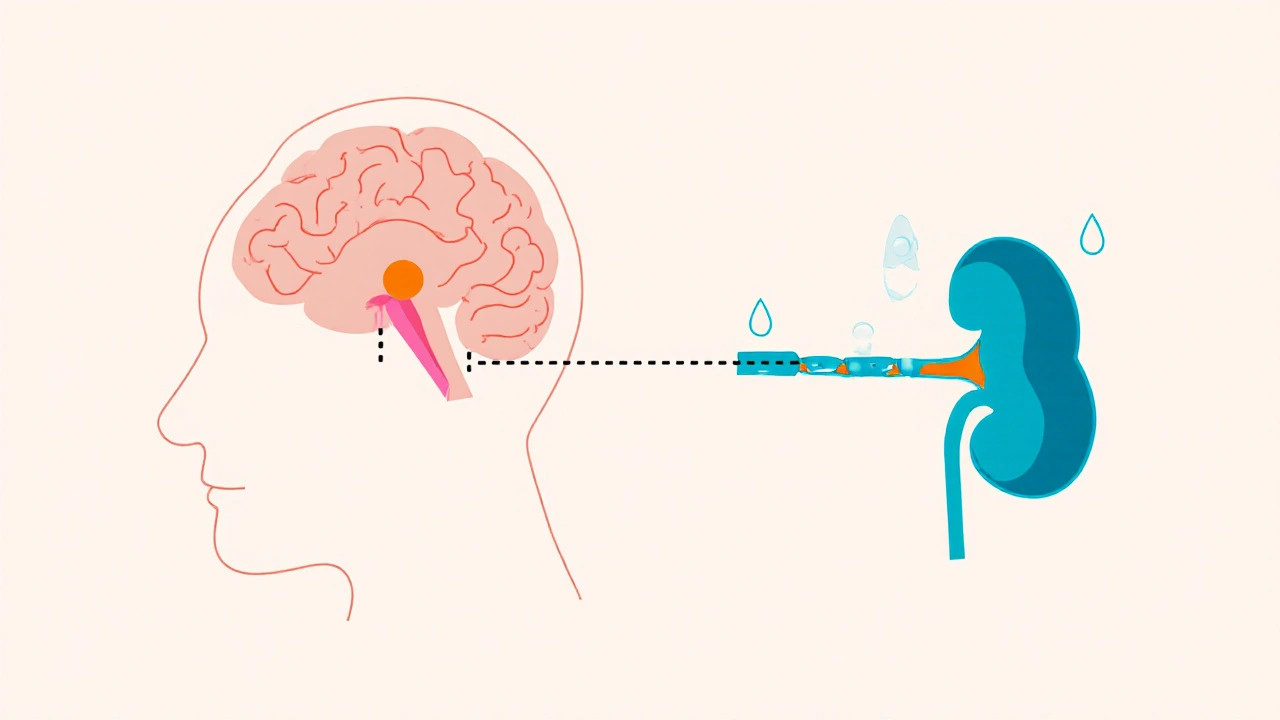

When working with vasopressin, a peptide hormone that tells the kidneys to reabsorb water, also known as antidiuretic hormone, the primary regulator of fluid balance, you quickly see how it ties into several medical scenarios. Vasopressin controls how much water stays in your bloodstream, so any excess or shortage can tip the scale toward conditions like SIADH, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion or diabetes insipidus, where the hormone is missing or ineffective. The hormone works through three main receptors – V1a, V1b and V2 – each triggering a different cellular response, from narrowing blood vessels to opening water channels in kidney cells.

Why Vasopressin Matters in Everyday Medicine

Understanding vasopressin opens the door to several therapeutic options. Synthetic versions such as desmopressin, a V2‑selective agonist, are used to treat central diabetes insipidus and to control bleeding in certain surgeries. On the flip side, antagonists like conivaptan and tolvaptan help manage hyponatremia caused by SIADH by blocking the V2 receptor and promoting water excretion. In critical care, low‑dose vasopressin infusions can support blood pressure when catecholamines aren’t enough, thanks to its V1a‑mediated vasoconstriction. These examples illustrate three clear semantic connections: vasopressin regulates water balance, SIADH involves excess vasopressin, and vasopressin antagonists treat SIADH.

Diagnosing a vasopressin‑related problem starts with a simple serum sodium test and a measurement of urine osmolality. In SIADH you’ll see low serum sodium, concentrated urine, and normal kidney function. In diabetes insipidus, the opposite pattern emerges – high serum sodium, dilute urine, and excessive thirst. Recognizing these lab patterns saves time and prevents inappropriate fluid therapy, which can worsen the underlying imbalance. Clinicians also consider medication‑induced changes; drugs like carbamazepine can raise vasopressin levels, while high‑dose corticosteroids may suppress its release.

Dosage and safety are crucial when you move from diagnosis to treatment. Desmopressin is typically started at 0.1 mg orally at night for diabetes insipidus, but the dose may need adjustment based on urine output and serum sodium. Over‑replacement can lead to water intoxication, seizures, or hyponatremia, especially in the elderly. Vasopressin infusions in the ICU are usually started at 0.01–0.04 units/min, with close monitoring of blood pressure and urine output to avoid excessive vasoconstriction, which could compromise organ perfusion.

Beyond the classic hormone‑related disorders, vasopressin shows up in a surprising range of clinical topics. Its vasoconstrictive action helps stabilize blood pressure during septic shock, while its role in water retention can affect outcomes in heart failure patients who also struggle with sleep‑related breathing disorders like sleep apnea. In fact, some of the articles in this collection compare vasopressin‑based therapies to other drug classes, explore side‑effect profiles, and break down cost versus benefit for different patient populations. Whether you’re a pharmacist looking for a price‑effective analog, a nurse managing infusion rates, or a physician deciding between an antagonist and fluid restriction, these posts give you practical, evidence‑based insights.

Below you’ll find a curated list of posts that dive deeper into each of these angles. You’ll see side‑by‑side drug comparisons, step‑by‑step dosing guides, safety checklists, and real‑world case studies that bring the science to life. Browse the collection to sharpen your understanding of how vasopressin works, when to intervene, and which treatment pathway fits your patient’s unique needs.