When a generic drug hits the market, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators make sure it does? Traditional bioequivalence tests look at two numbers: total AUC (how much drug gets into your bloodstream over time) and Cmax (how high the peak concentration goes). For simple pills, that’s often enough. But for complex formulations-like extended-release painkillers, abuse-deterrent opioids, or mixed-mode drugs-those two numbers can lie. That’s where partial AUC comes in.

Why Traditional Metrics Fail for Complex Drugs

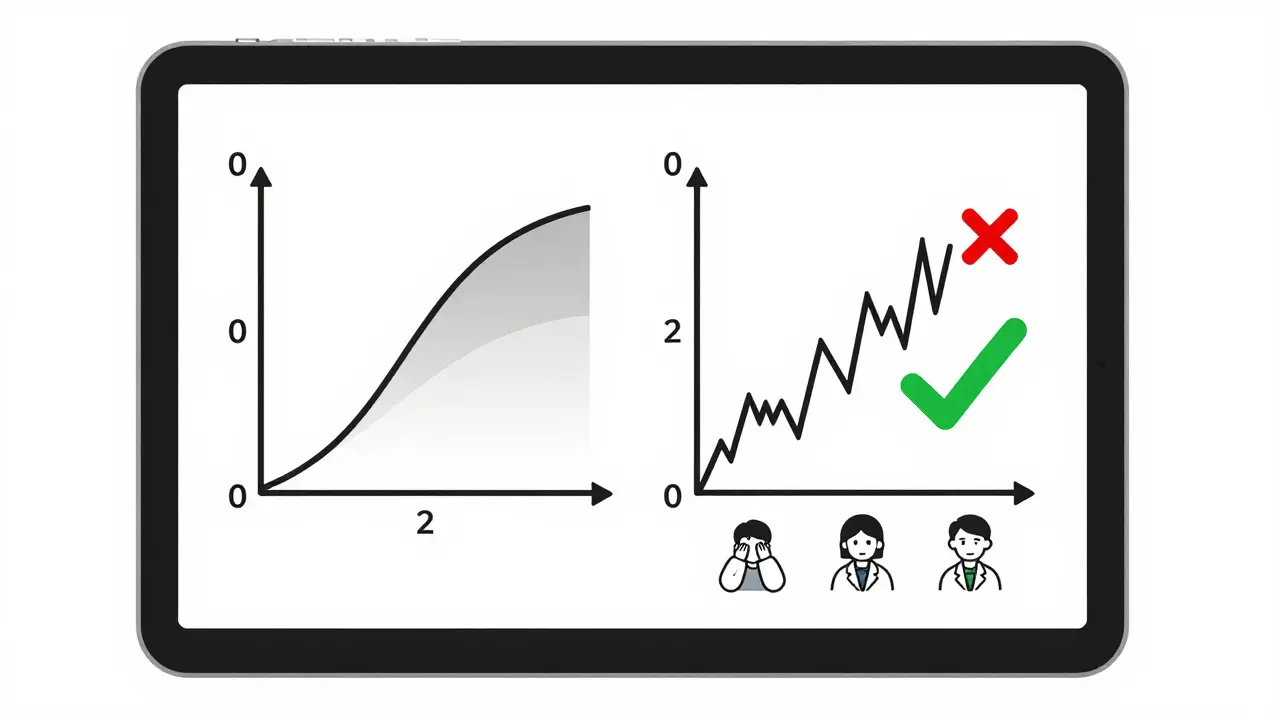

Imagine two painkillers. One releases its drug slowly over 12 hours. The other has a quick burst, then a slow release. Both might have the same total AUC and the same Cmax. But if the first one spikes too fast, it could be abused. If the second one takes too long to kick in, the patient suffers. Traditional metrics can’t tell the difference. They see the same total exposure, so they call them equivalent. But clinically? They’re not. This isn’t hypothetical. In 2014, a study in the European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences found that 20% of generic drugs that passed standard bioequivalence tests would have failed if partial AUC had been used. When researchers looked at both fasting and fed conditions together, that failure rate jumped to 40%. That’s a huge gap between what regulators thought was safe and what actually happened in the body.What Is Partial AUC?

Partial AUC, or pAUC, measures drug exposure only during a specific time window-not the whole curve. It’s like zooming in on the most important part of the graph. For an extended-release drug, that window might be the first 2 hours after dosing, when absorption is happening and differences between products matter most. For abuse-deterrent formulations, it’s often the first 30 to 60 minutes, when someone might try to crush or snort the pill. The FDA started pushing for pAUC after its 2017 Quantitative Modeling Workshop. They called it an “improved metric” because it’s sensitive to differences where they count-high concentration zones-and ignores noise where it doesn’t. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) followed in 2013, specifically calling out prolonged-release formulations as needing this level of scrutiny.How Is pAUC Calculated?

There’s no single way to define the time window. The FDA says it should be tied to a clinically relevant effect-like when the drug starts working or when abuse risk is highest. In practice, that means using one of three common methods:- From time zero to the Tmax of the reference product (the time it takes to reach peak concentration)

- From time zero to a percentage of Cmax (like 50% of the peak)

- From time zero to when drug concentration drops below a certain level

When Is pAUC Required?

It’s not used for every drug. But if your product falls into one of these categories, you’re almost certainly going to need it:- Extended-release or modified-release formulations

- Abuse-deterrent opioids (like OxyContin generics)

- Mixed-mode drugs (immediate + extended release in one pill)

- CNS drugs (for conditions like epilepsy, Parkinson’s, or depression)

- Cardiovascular drugs with narrow therapeutic windows

Real-World Impact: Cost, Time, and Failure

Implementing pAUC isn’t cheap. A senior biostatistician at Teva reported that adding pAUC to their extended-release opioid study increased the sample size from 36 to 50 subjects. That added $350,000 to the development cost. But it also prevented a clinical failure. Without pAUC, they might have missed a 22% difference in early exposure-enough to cause underdosing or overdose in real patients. On the flip side, 17 ANDA submissions were rejected in 2022 just because the pAUC time window was poorly defined. Generic companies are struggling with inconsistent guidance. Only 42% of FDA product-specific guidances clearly explain how to pick the right cutoff time. Some use Tmax. Others use Cmax percentages. There’s no universal standard.

Who’s Using It? Who’s Struggling?

Big pharma and large generic manufacturers have teams of pharmacokinetic experts, advanced software (like Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM), and statistical consultants. They’re adapting. But smaller firms? They’re getting left behind. A 2022 survey by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 63% of companies needed extra statistical help for pAUC-compared to just 22% for traditional metrics. Job postings tell the same story. In 2023, 87% of bioequivalence specialist roles listed pAUC expertise as required. If you’re in this field, you need to know how to define time intervals, run nonlinear mixed-effects models, and interpret confidence intervals using the Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller method. It’s not something you learn in a weekend.The Future of Bioequivalence

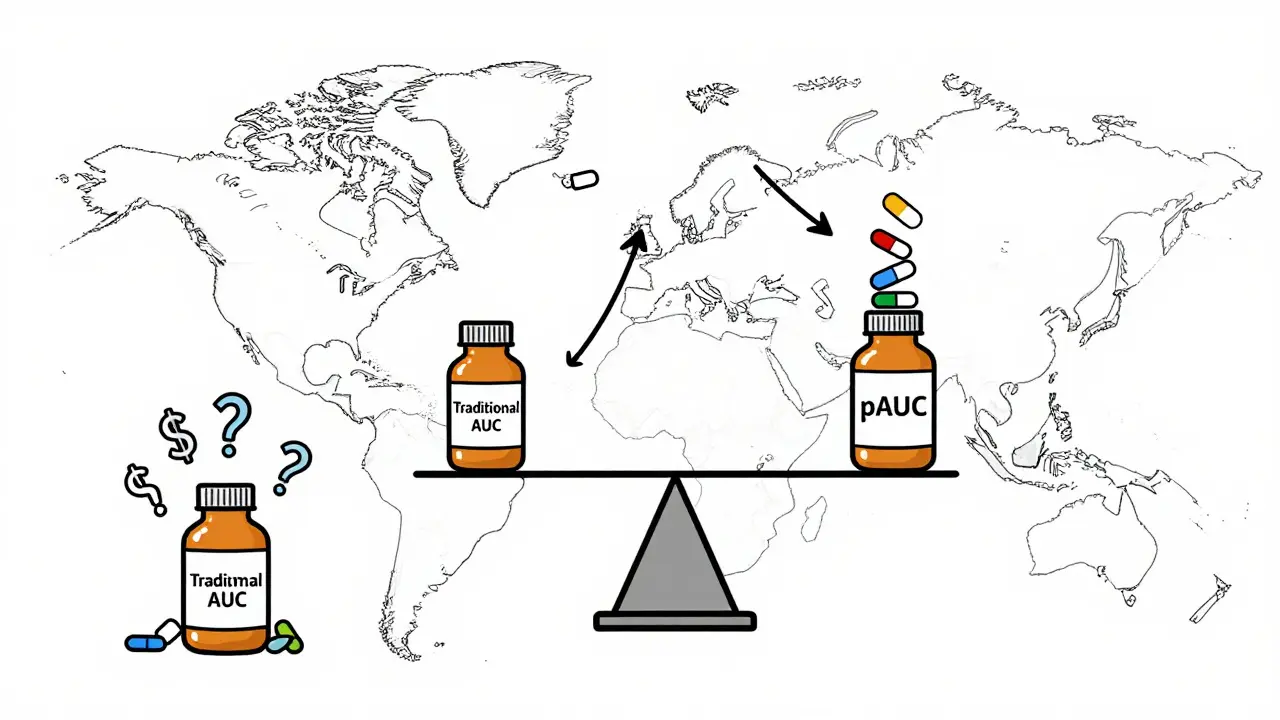

The FDA is working on solutions. In early 2023, they launched a pilot program using machine learning to automatically determine optimal pAUC time windows based on reference product data. That could standardize the process and reduce subjectivity. The goal? Better drugs. Safer generics. Fewer clinical failures. The science behind pAUC is solid. The FDA’s 2021 white paper called it “scientifically sound and necessary.” The EMA agrees. And industry data shows adoption is accelerating. But the road ahead isn’t smooth. Without clearer guidelines, inconsistent methods, and higher costs, smaller companies will keep falling behind. Global development timelines are already 12-18 months longer because of conflicting pAUC rules across the U.S., EU, and other regions.Bottom Line

Partial AUC isn’t just another statistic. It’s a shift in how we think about bioequivalence. For simple drugs, traditional metrics still work fine. But for anything complex-anything that needs to release slowly, safely, or predictably-pAUC is no longer optional. It’s the new baseline. If you’re developing, reviewing, or prescribing generic drugs, you need to understand it. Because the next time a patient says their generic isn’t working the same, the answer might not be in the total exposure. It might be in the first hour.What is the main purpose of partial AUC in bioequivalence studies?

Partial AUC measures drug exposure only during a specific, clinically relevant time window-like the first 2 hours after dosing-instead of the entire concentration-time curve. This helps regulators detect differences in how quickly a drug is absorbed, especially for extended-release or abuse-deterrent formulations where traditional metrics like total AUC and Cmax may miss critical performance gaps.

How is the time window for partial AUC determined?

The time window is typically based on the reference product’s Tmax (time to peak concentration), a percentage of Cmax (like 50%), or a concentration threshold tied to a known pharmacodynamic effect. The FDA recommends linking the window to a clinically relevant outcome-such as when the drug starts working or when abuse risk is highest-to ensure the measurement reflects real-world performance.

Is partial AUC required for all generic drugs?

No. Partial AUC is only required for complex formulations where traditional metrics are insufficient-such as extended-release, abuse-deterrent, or mixed-mode drugs. As of 2023, the FDA mandates pAUC for 127 specific products, mostly in pain management, CNS disorders, and cardiovascular categories. Most simple immediate-release generics still use only total AUC and Cmax.

Why does partial AUC increase study costs?

Because pAUC is more sensitive to small differences, it often has higher variability. To achieve statistical power, studies typically need 25-40% more participants than traditional bioequivalence trials. For example, a study that previously needed 36 subjects may now require 50 or more, adding hundreds of thousands of dollars to development costs.

What tools are needed to analyze partial AUC data?

Advanced pharmacokinetic software like Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM is essential. Analysts must also understand nonlinear mixed-effects modeling and be proficient in calculating confidence intervals using the Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller method. Many biostatisticians require 3-6 months of specialized training to become competent in pAUC analysis.

Are there differences between FDA and EMA guidelines for pAUC?

Yes. While both agencies agree on the scientific value of pAUC, their guidance documents differ in specificity. The EMA introduced pAUC in 2013 for prolonged-release formulations and now recommends it for 27 product categories. The FDA has expanded its use to 127 specific products as of 2023, but only 42% of its product-specific guidances clearly define how to choose the time window, leading to implementation uncertainty.

How has pAUC improved drug safety?

pAUC has prevented unsafe generics from reaching the market by catching differences in early drug exposure that traditional metrics missed. One AAPS case study showed a 22% difference in early absorption between a test and reference opioid product-undetectable by total AUC alone. That difference could have led to underdosing or overdose in patients. pAUC made the risk visible and allowed regulators to block the product.

What’s the future of partial AUC in regulatory science?

The FDA is developing machine learning tools to automatically determine optimal pAUC time windows based on reference product data, aiming to standardize the process. By 2027, Evaluate Pharma predicts that 55% of all new generic approvals will require pAUC analysis. As complexity in drug formulations grows, pAUC will become the norm-not the exception-for ensuring therapeutic equivalence.

9 Comments

So they're just making us pay more for generics because Big Pharma wants to keep their patents? Feels like a cash grab disguised as science.

theyre hiding the truth again lol. why do u think the fda only started pushin pAUC after 2017? coincidence? nah. big pharma paid them off. u think they care if some kid overdoses on a fake oxy? nope. just want their cut. #pharmabullshit

Oh please. If you can't even get the timing right on your pain med, you're gonna have a bad time. This isn't rocket science, it's basic pharmacokinetics. Stop acting like this is some new conspiracy.

Let me get this straight - the FDA, the most transparent agency in the world, is suddenly being manipulated by foreign drug manufacturers? No. This is American science protecting American patients. The EMA? They're still stuck in 2005. We're leading the world here, and if you're mad about the cost, blame the companies that can't keep up - not the regulators doing their job.

They call it 'scientifically sound' but let's be real - this is just another way to delay generics so brand-name companies can keep jacking up prices. And don't even get me started on how they pick these 'clinically relevant windows.' One day it's Tmax, the next it's 50% of Cmax - it's all just smoke and mirrors to protect Big Pharma's bottom line. Wake up, people. This isn't safety, it's corporate control.

I've seen the data. The same labs that wrote the guidelines also consult for the big pharma giants. Conflict of interest? More like a revolving door with a golden handcuff.

And now they want to use AI to pick the windows? Brilliant. Let’s just let the same corporations who profit from delays train the algorithm. Of course they'll optimize it to favor their own products. This isn't innovation - it's institutionalized corruption.

Meanwhile, real people are getting sick because their generics don't work the same. But hey, at least the FDA’s got a fancy new acronym to brag about at their next gala dinner.

Remember when they said GMOs were safe? Or that vaping was harmless? We were told the same things. And look where we are now. History doesn't repeat - it rhymes. And this? This is a damn sonnet.

It's wild how much more complex this has gotten since I started in biostats 10 years ago. Back then we just did AUC and Cmax and called it a day. Now you need a whole team just to define the time window. And don't even get me started on the Bailer-Satterthwaite-Fieller method - I still have nightmares about that one

But honestly? I get why. I worked on a project where the generic looked identical on paper but patients were crashing on it. Turned out the early absorption was off by 30%. Without pAUC we never would've caught it. It's painful and expensive but it's saving lives

So basically they're saying if your painkiller doesn't kick in fast enough, it's not safe? That makes sense for opioids but what about arthritis meds? I take one that's supposed to be slow - why would I want it to spike?

Also why do we need 50 people for a study when 36 used to work? Are we just making up variability to justify higher costs?

Still, I'm glad they're paying attention to real-world effects. My grandma took a generic that 'passed' but made her dizzy. This might've caught that.

Just read this and realized I've been on three different generics for my epilepsy med and they all feel different. I thought it was just me. Turns out maybe it wasn't. This makes so much sense now. I hope more docs start asking about pAUC when they prescribe

Thank you for this thorough and well-structured overview. The evolution from total AUC to partial AUC represents a significant advancement in regulatory science, grounded in clinical reality rather than statistical convenience. The increased sample size requirements, while financially burdensome, are a necessary investment in patient safety. As professionals in this field, we must advocate for standardized methodologies and adequate resources to ensure equitable access to high-quality generics across all manufacturers, regardless of size. The goal is not merely compliance - it is therapeutic equivalence in practice, not just on paper.