When you take multiple medications, the risk of dangerous drug interactions doesn’t just depend on what pills you’re on-it also depends on your genes. Two people taking the exact same combination of drugs can have wildly different outcomes because of their genetic makeup. This isn’t science fiction. It’s pharmacogenomics, and it’s changing how we predict and prevent harmful drug interactions.

What Pharmacogenomics Actually Means

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how your genes affect how your body responds to drugs. It’s not just about one gene or one drug-it’s about the whole system. Your DNA determines how fast or slow you break down medications, how sensitive you are to their effects, and even whether a drug might cause a dangerous reaction. For example, some people have a genetic variant that makes them metabolize codeine extremely fast, turning it into morphine too quickly and causing life-threatening breathing problems. Others can’t break it down at all, so it does nothing. The same drug, two completely different outcomes-all because of genes.

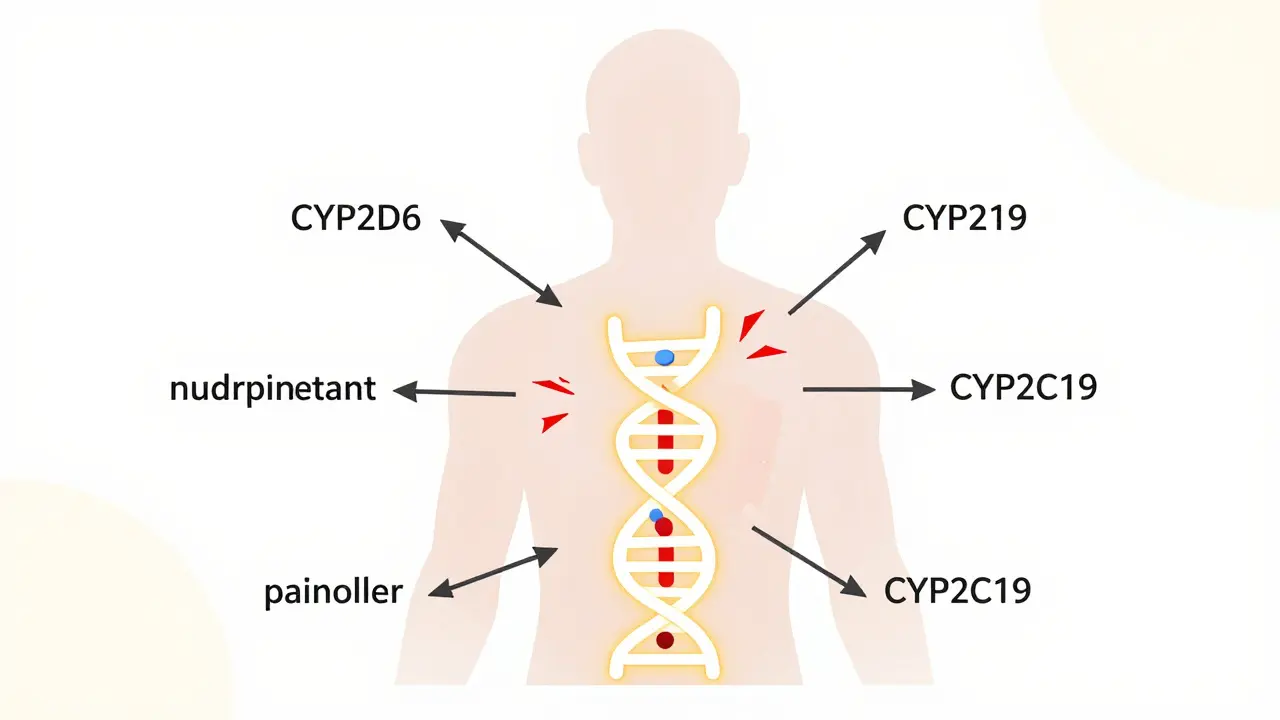

This isn’t rare. The FDA lists over 148 gene-drug pairs with clear clinical meaning. That means for more than 140 different drugs, your genetic profile directly affects whether the drug works, how much you need, or whether it’s dangerous. The most common genes involved? CYP2D6 and CYP2C19. These code for liver enzymes that handle about 25% of all commonly prescribed medications, including antidepressants, blood thinners, and painkillers.

How Genes Make Drug Interactions Worse

Drug interactions usually happen when one drug interferes with how another is processed. But pharmacogenomics adds a whole new layer. Imagine you’re a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer-you naturally break down certain drugs very slowly. Now you take an antidepressant that also blocks CYP2D6. That’s not just a drug-drug interaction. That’s a gene-drug-drug interaction. Your body already can’t handle the drug well. The second drug makes it worse. The result? Toxic levels build up. You could end up in the hospital.

This is called phenoconversion. Your genetic phenotype says you’re slow. But a drug temporarily turns you into an even slower metabolizer. It’s like having a leaky faucet and then turning the water pressure up full blast. The system overflows. Studies show this kind of interaction increases the risk of serious side effects by more than 30% in people taking three or more medications.

And it’s not just metabolism. Some genes affect how drugs bind to their targets. If you carry the HLA-B*15:02 variant, taking carbamazepine-a common seizure and bipolar drug-can trigger Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, a deadly skin reaction. Your genes don’t just change how the drug moves through your body. They change how your immune system reacts to it.

Why Traditional Drug Interaction Checkers Fall Short

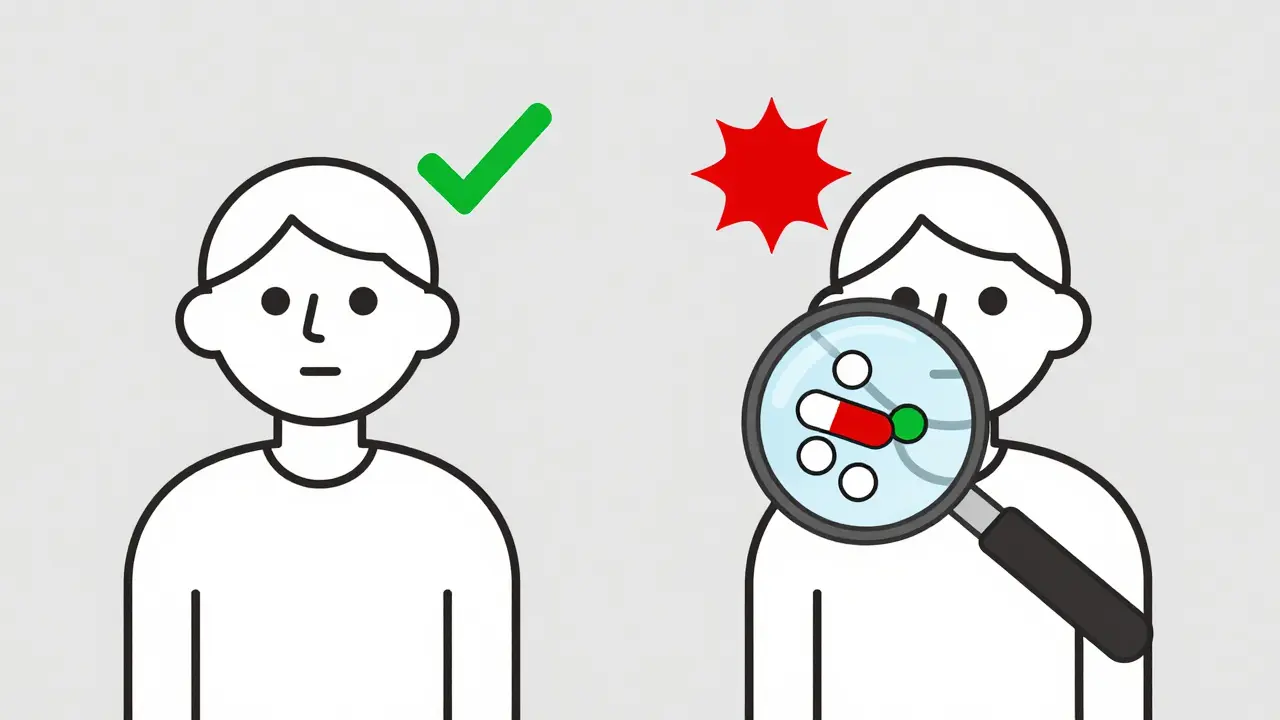

Most pharmacy systems use tools like Lexicomp or Micromedex to warn about drug interactions. They’re useful. But they don’t know who you are. They don’t know your genes. They just say, “This combo might be risky.” But for most people, it’s not. For a small group-those with certain genetic variants-it’s extremely risky.

A 2022 study in the American Journal of Managed Care looked at over 10,000 patients in community pharmacies. When they added genetic data, the number of high-risk interactions jumped by 90%. That’s not a small tweak. That’s a complete overhaul of risk assessment. Without genetics, you’re guessing. With genetics, you’re seeing the real picture.

Take warfarin, the blood thinner. Traditional dosing relies on age, weight, and diet. But adding CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic testing cuts the risk of major bleeding by 31% and gets patients into the safe range faster. The FDA says these genes matter. Yet most hospitals still don’t test for them.

Where Pharmacogenomics Is Already Working

At Mayo Clinic, they’ve been doing preemptive pharmacogenomic testing since 2011. That means they test patients for key gene variants before prescribing any drugs. The results? 89% of patients had at least one actionable result. When their electronic health record flagged a potential gene-drug interaction, doctors changed prescriptions 45% of the time. That’s not just theory. That’s real people avoiding hospital stays.

Vanderbilt’s PREDICT program has tested over 100,000 patients. They found that 60% of those with a genetic risk for adverse reactions were never flagged by standard drug interaction systems. That’s a huge blind spot. And it’s not just big hospitals. The Cleveland Clinic, Stanford, and even some VA medical centers now routinely test for genes like TPMT before prescribing azathioprine. Without testing, a single dose could wipe out a patient’s bone marrow. With testing? Safe, effective treatment.

The Gap Between Science and Practice

Despite the evidence, most doctors still don’t use pharmacogenomics. Why? Three big reasons.

First, lack of training. A 2023 survey of 1,200 pharmacists found only 28% felt confident interpreting genetic reports. Most weren’t taught this in school. Second, no integration. If your genetic result sits in a separate portal and your EHR doesn’t alert you, it’s useless. Third, reimbursement. Most insurers only cover PGx testing for a handful of drugs, like clopidogrel or certain antidepressants. The test itself costs $250-$400. If the insurance won’t pay, patients often don’t get tested.

And there’s another problem: bias. Over 90% of pharmacogenomic research has been done in people of European descent. That means guidelines for CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 might not work for African, Asian, or Indigenous populations. A 2023 study in Cell Genomics found only 2% of PGx research participants had African ancestry. That’s not just a gap. It’s a danger.

What’s Next? AI, Regulation, and Real-World Change

The future is coming fast. The NIH’s All of Us program has returned PGx results to over 250,000 people. The FDA plans to add 24 new gene-drug pairs to its list in 2024. And AI is stepping in. A 2023 study showed an AI model using genetic data predicted warfarin dosing 37% more accurately than standard methods. That’s not just better-it’s life-saving.

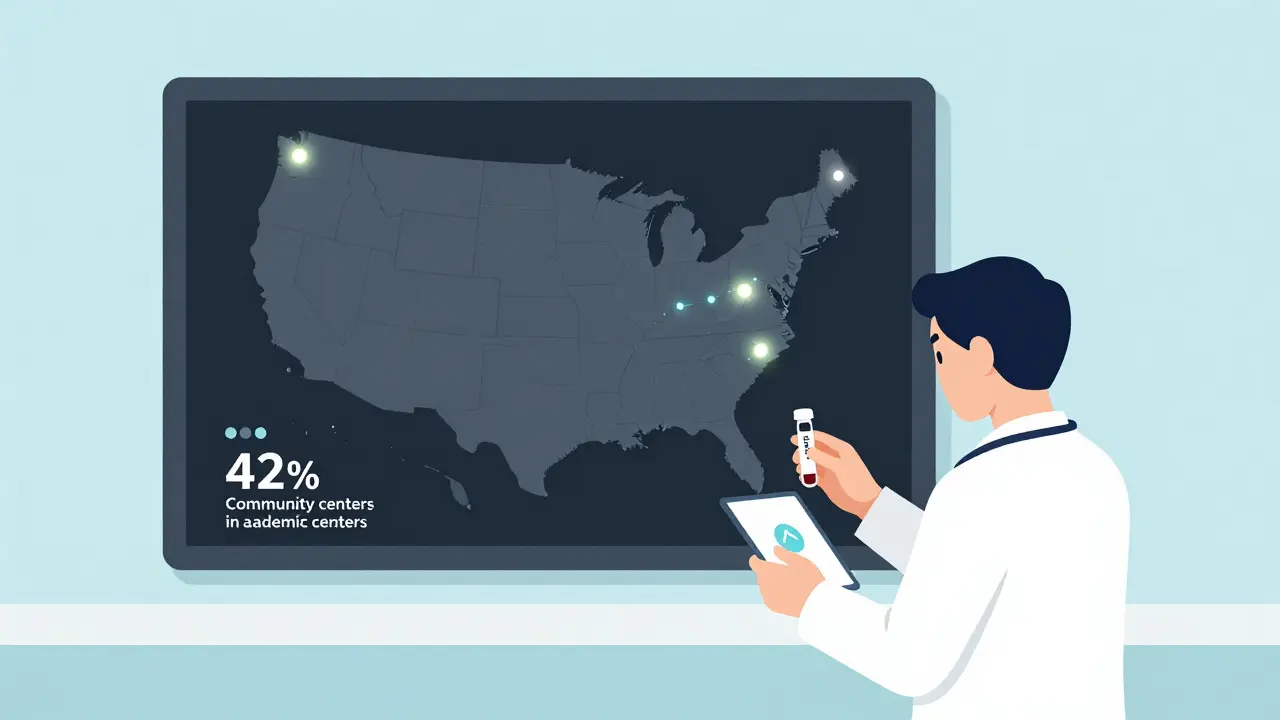

Regulators are catching up too. The European Medicines Agency now says pharmacogenomics is a key factor in drug interaction risk. Pharmaceutical companies are being pushed to study genetic effects before approval. But progress is uneven. Only 42% of U.S. academic medical centers offer testing. In community hospitals? Just 8%.

The solution isn’t just more tests. It’s smarter systems. EHRs that auto-alert when a gene-drug conflict is likely. Pharmacist-led PGx clinics. Insurance coverage that expands beyond a few drugs. And training that makes genetics part of every prescriber’s toolkit.

What You Can Do

If you’re on three or more medications, especially for chronic conditions like depression, heart disease, or pain, ask your doctor: “Have you checked if my genes affect how these drugs work?” If you’ve had a bad reaction to a drug before, or if a medication didn’t work even at high doses, that’s a red flag. Your genes might hold the answer.

Companies like 23andMe and Ancestry now offer limited pharmacogenomic reports. They’re not a full clinical test-but they can spark a conversation with your doctor. If you’re considering genetic testing, look for labs that follow CPIC guidelines. That means they use standardized definitions for gene variants and translate them into clear, actionable advice.

This isn’t about replacing your doctor. It’s about giving them better tools. Pharmacogenomics doesn’t make medicine more complicated. It makes it more precise. And precision saves lives.

How does pharmacogenomics reduce the risk of drug interactions?

Pharmacogenomics identifies genetic variants that affect how your body processes drugs. For example, if you’re a slow metabolizer of CYP2D6, certain drugs can build up to toxic levels. By knowing your genetic profile, doctors can avoid prescribing drugs that interact dangerously with your genes or adjust doses to prevent harm. This cuts down on unpredictable interactions that standard drug interaction checkers miss.

Which genes are most important for drug interactions?

CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 are the top two. They handle about 25% of all commonly prescribed medications, including antidepressants, beta-blockers, painkillers, and anti-seizure drugs. Other key genes include TPMT (for chemotherapy and immune drugs), VKORC1 (for warfarin), and HLA-B*15:02 (for carbamazepine). These variants are well-documented and have clear clinical guidelines.

Can pharmacogenomics prevent serious side effects like bleeding or skin reactions?

Yes. For example, testing for HLA-B*15:02 before prescribing carbamazepine prevents Stevens-Johnson Syndrome in high-risk patients. Testing for TPMT before azathioprine avoids life-threatening bone marrow suppression. Studies show PGx-guided dosing reduces major bleeding from warfarin by 31% and cuts overall adverse drug reactions by over 30% in polypharmacy patients.

Why don’t all doctors use pharmacogenomic testing?

Three main reasons: lack of training, no integration into electronic health records, and poor insurance coverage. Only 15% of U.S. healthcare systems have PGx alerts built into their systems. Most doctors aren’t taught how to interpret genetic reports. And without reimbursement, patients often can’t afford the test-even though it can prevent costly hospitalizations later.

Are pharmacogenomic guidelines the same for everyone?

Not yet. Most guidelines are based on data from people of European ancestry. This means they may not accurately predict risk for African, Asian, or Indigenous populations. For example, CYP2D6 variants common in East Asian populations aren’t always covered in standard tests. Research is expanding, but until testing includes diverse groups, there’s a risk of misapplication and health disparities.