When someone experiences their first episode of psychosis, everything changes-fast. They might hear voices no one else hears, believe things that aren’t true, or struggle to speak clearly. Their world feels broken. And if no one steps in quickly, it can stay broken for years. But here’s the truth: first-episode psychosis doesn’t have to mean a lifetime of illness. With the right help in the first few months, many people recover fully, go back to school, get jobs, and rebuild their lives.

What Happens During a First Psychotic Episode?

A first-episode psychosis isn’t just being ‘a little off.’ It’s when the brain starts misfiring in ways that blur the line between reality and imagination. Someone might hear footsteps when no one’s there, think strangers are watching them, or believe they have special powers. They might withdraw from friends, stop showering, or talk in ways that don’t make sense. These aren’t choices-they’re symptoms of a brain in distress. It usually hits between ages 15 and 30. Young adults, often just starting college or their first job, are most at risk. And the longer these symptoms go untreated, the harder it becomes to recover. Studies show that if someone waits more than six months to get help, their brain loses ground they may never fully regain. That’s why timing isn’t just important-it’s everything.Why Early Intervention Works

The National Institute of Mental Health’s RAISE project, which tracked over 400 people with first-episode psychosis, proved something revolutionary: early, coordinated care changes outcomes. People who got help within 12 weeks were far more likely to stay in school, hold jobs, and avoid hospital stays compared to those who waited. This isn’t guesswork. It’s science. Coordinated Specialty Care (CSC) teams-made up of psychiatrists, therapists, case managers, and peer support specialists-work together to deliver five key services:- Medication management: Antipsychotics are used at the lowest effective dose. High doses? They increase side effects without helping more. NICE guidelines specifically warn against them.

- Therapy tailored for psychosis: Cognitive behavioral therapy helps people understand their symptoms, reduce fear, and build coping skills-not just suppress them.

- Case management: Someone is assigned to help with appointments, housing, transportation. No one gets lost in the system.

- Supported education and employment: The Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model helps people return to school or work. In CSC programs, 50-60% land competitive jobs. In traditional care? Only 20-30%.

- Family support: This isn’t optional. It’s essential.

The Critical Role of Family Support

Families are often the first to notice something’s wrong. But they’re also the most confused. They might think their child is just being dramatic, lazy, or rebellious. Or worse-they blame themselves. Family psychoeducation changes that. It’s not about giving advice. It’s about teaching families what psychosis really is, how to respond without escalating tension, and how to support recovery without enabling illness. Studies show that when families attend at least 8-12 structured sessions over six months, relapse rates drop by 25%. That’s huge. When a mother learns to say, “I see you’re feeling scared right now,” instead of “Stop talking like that,” it reduces stress for everyone. When a father understands that hallucinations aren’t lies-they’re real experiences to the person having them-it opens the door to trust. And it’s not just emotional. Families help with practical things: reminding someone to take meds, driving them to appointments, helping them cook meals when they’re too overwhelmed. In Washington State’s New Journeys program, family involvement was one of the top reasons clients stayed in treatment longer.What Happens If You Wait?

Delaying treatment isn’t just risky-it’s costly. Literally. The average person with untreated psychosis spends years bouncing between ERs, jails, homeless shelters, and outpatient clinics that don’t know how to help. The U.S. spends $155.7 billion a year on the fallout of untreated psychosis-mostly from lost wages, emergency care, and incarceration. With early intervention, that drops to $28.5 billion. And the human cost? Even worse. Someone who waits a year to get help is 40% less likely to return to school or work. Their chances of living independently drop by half. Their risk of suicide rises. The brain has a window-about three to six months-where it’s still responsive to treatment. After that, neural pathways start hardening. Recovery isn’t impossible, but it becomes harder, slower, and more expensive.Barriers to Getting Help

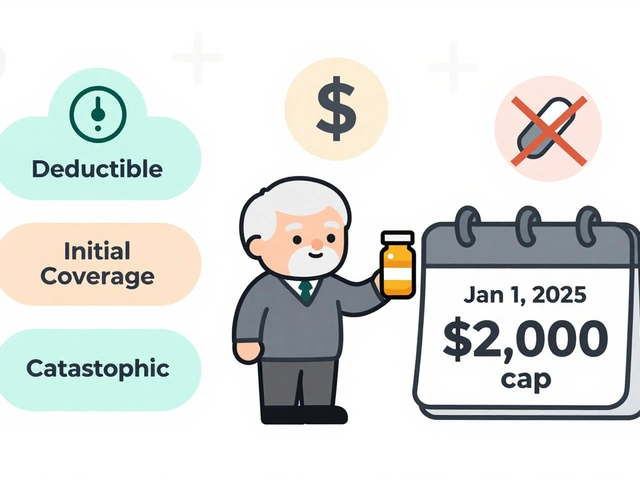

The science is clear. The treatment works. So why don’t more people get it? First, access. Only 35% of U.S. counties have a certified CSC program. In rural areas, that number drops to 38%-meaning two out of every three people in the countryside have no access to evidence-based care. Second, funding. CSC costs $8,000-$12,000 per person per year. Standard care? $5,000-$7,000. Insurance companies balk. Only 31 states have Medicaid waivers covering all CSC services. That means families often pay out of pocket-or give up. Third, stigma. Many people still think psychosis means “crazy.” They don’t realize it’s a medical condition, like diabetes or epilepsy. And because of that, families wait too long to seek help-hoping it’ll pass.

What’s Working Right Now

Some places are beating the odds. Louisiana’s mobile crisis units respond to psychosis calls within 14 days. That’s faster than most people can get a doctor’s appointment for a sprained ankle. Washington State’s New Journeys program has cut the average time between first symptoms and treatment from 78 weeks to just 26. Their teams hit 95% fidelity scores on quality checks. That’s rare. Telehealth is helping too. During the pandemic, family sessions moved online-and participation jumped 35%. Now, many programs keep it as an option. And digital tools are coming. Apps like PRIME Care let people log their moods, sleep, and symptoms daily. Early trials show a 30% drop in hospitalizations. That’s not sci-fi-it’s happening now.What You Can Do

If you’re worried about someone you love:- Don’t wait. If symptoms last more than two weeks, call a mental health provider-even if you’re not sure.

- Find a CSC program. The Early Psychosis Intervention Network (EPINET) has a directory. Look for programs that offer all five core services.

- Ask about family sessions. Don’t assume they’re optional. Push for them.

- Learn about antipsychotics. Ask the doctor: ‘What dose are you starting with? Is it below the standard chronic dose?’ High doses hurt more than help.

- Connect with others. Groups like NAMI offer free family training. You’re not alone.

The Future Is Here-If We Choose It

We know what works. We have the tools. We have the data. What’s missing is willpower. Right now, only 18% of first-episode psychosis cases get treated within the WHO’s recommended 12-week window. That means four out of five people are falling through the cracks. But change is possible. With more funding, better training for providers, and public education to break stigma, we can get that number to 80%. We can turn first-episode psychosis from a life sentence into a turning point. It starts with one question: What if we acted fast-not just when things get bad, but when they first start to go wrong?What are the first signs of psychosis?

Early signs include social withdrawal, trouble sleeping, unusual thoughts or beliefs (like thinking people are spying on you), decreased motivation, difficulty concentrating, and speech that becomes vague or hard to follow. These often appear gradually over weeks or months-not suddenly. If they last more than two weeks, it’s time to seek help.

Is psychosis the same as schizophrenia?

No. Psychosis is a symptom-not a diagnosis. Schizophrenia is one possible diagnosis after multiple psychotic episodes. Many people have one episode of psychosis and never have another. Early intervention reduces the chance it turns into a long-term condition.

Can medication cure psychosis?

Medication doesn’t cure psychosis, but it helps manage symptoms. The goal isn’t to numb someone-it’s to reduce distress so they can engage in therapy, return to school or work, and rebuild their life. Low-dose antipsychotics are preferred for first episodes to avoid side effects like weight gain or diabetes.

Why is family involvement so important?

Families are often the first to notice symptoms and the most consistent source of support. When they understand psychosis, they respond with compassion instead of fear. Studies show family psychoeducation cuts relapse rates by 25% and helps the person stay in treatment longer. It’s not about fixing them-it’s about walking alongside them.

How do I find a Coordinated Specialty Care program near me?

Visit the Early Psychosis Intervention Network (EPINET) website or call the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) helpline. Look for programs that offer medication management, therapy, case management, supported employment, and family education. Ask if they’re certified and how long their average time-to-treatment is.

Is early intervention only for young people?

While most first episodes happen between ages 15 and 30, anyone can experience psychosis for the first time at any age. The principles of early intervention apply to all ages. However, the strongest evidence and most structured programs focus on youth and young adults because early treatment in this group has the biggest impact on long-term outcomes.

What if the person doesn’t want help?

It’s common for people in early psychosis to lack insight into their symptoms. Don’t force it. Instead, stay connected. Offer support without pressure. Encourage them to talk to someone they trust-a teacher, coach, or doctor. Sometimes, a single conversation with a non-threatening professional can open the door. Mobile crisis teams can also help assess safely at home.

12 Comments

This hit me hard. My cousin went through this last year. We didn’t know what was happening until it was too late. I wish we’d known about CSC sooner. 🙏

Oh wow. So we’re spending $155B on ignoring mental health like it’s a moral failing and not a fucking medical condition? And you’re surprised people end up in jail? 😒

CSC is overhyped. Most studies are funded by pharma. Low-dose antipsychotics? More like gateway drugs. Also, 'family psychoeducation' sounds like gaslighting with a PowerPoint.

Let’s be real - this isn’t about treatment. It’s about social control. The system doesn’t want people to recover. It wants them docile. Psychosis? It’s not a disease. It’s a rebellion against a broken world. They medicate the messengers. The real illness is capitalism.

You’re all missing the point. This isn’t about funding or access. It’s about cultural decay. We’ve normalized isolation. We’ve replaced community with apps. When a young person breaks down, no one’s home to hold them. We stopped being human. The system didn’t fail - we did.

I work in community mental health. I’ve seen CSC turn lives around. One kid went from sleeping in his car to graduating with honors in 18 months. It’s not magic. It’s consistency. Compassion. Structure. We can do this. We just have to choose to.

I’ve been watching this for years. The government doesn’t want you to know this, but psychosis is linked to 5G towers and chemtrails. They use the term 'antipsychotics' to distract you. The real cure is grounding yourself in nature and eating raw garlic. Also, I’ve had 17 episodes and I’m still here. They’re scared of what happens when people wake up.

In India we say darr ke aage jeet hai - victory lies beyond fear. My sister heard voices for 8 months before we found help. No insurance. No CSC. Just my mom sitting with her every night talking about the stars. That’s what saved her. Not meds. Not programs. Presence.

The irony is thick here. You’re preaching 'early intervention' while ignoring that most psychosis cases stem from trauma, not biology. You’re pathologizing pain. You’re turning suffering into a diagnostic category so the state can manage it. This is neoliberal mental health industrial complex 101.

I’m a grad student in neuroethics. The real question isn’t whether CSC works - it’s who gets to define 'recovery.' Is it returning to work? Or is it learning to live with difference? The model assumes neurotypicality as the goal. What if psychosis isn’t a glitch - but a different operating system?

I’m a nurse in a CSC program. We had a 19-year-old who stopped showering, thought his phone was spying on him, and dropped out of college. After 12 weeks: he’s back in class, works part-time at a coffee shop, and texts me memes every Sunday. This works. I see it. Every day.

Brilliantly written. I’m from the UK - we’ve got similar programs here, but funding’s a mess. The NHS is stretched thin. Still, I’ve seen the difference. One thing I’d add: family sessions aren’t just helpful - they’re healing for the whole family. We forget that. Thank you for this.