When a pharmacist fills a prescription, they’re not just handing out pills-they’re making a decision that affects safety, cost, and patient trust. The difference between a brand-name drug and its generic version might seem simple, but in pharmacy systems, it’s anything but. One wrong code, one missed alert, one unexplained substitution-and you could be risking patient outcomes. This isn’t theory. It’s daily practice in pharmacies across the U.S.

Why Identification Matters More Than You Think

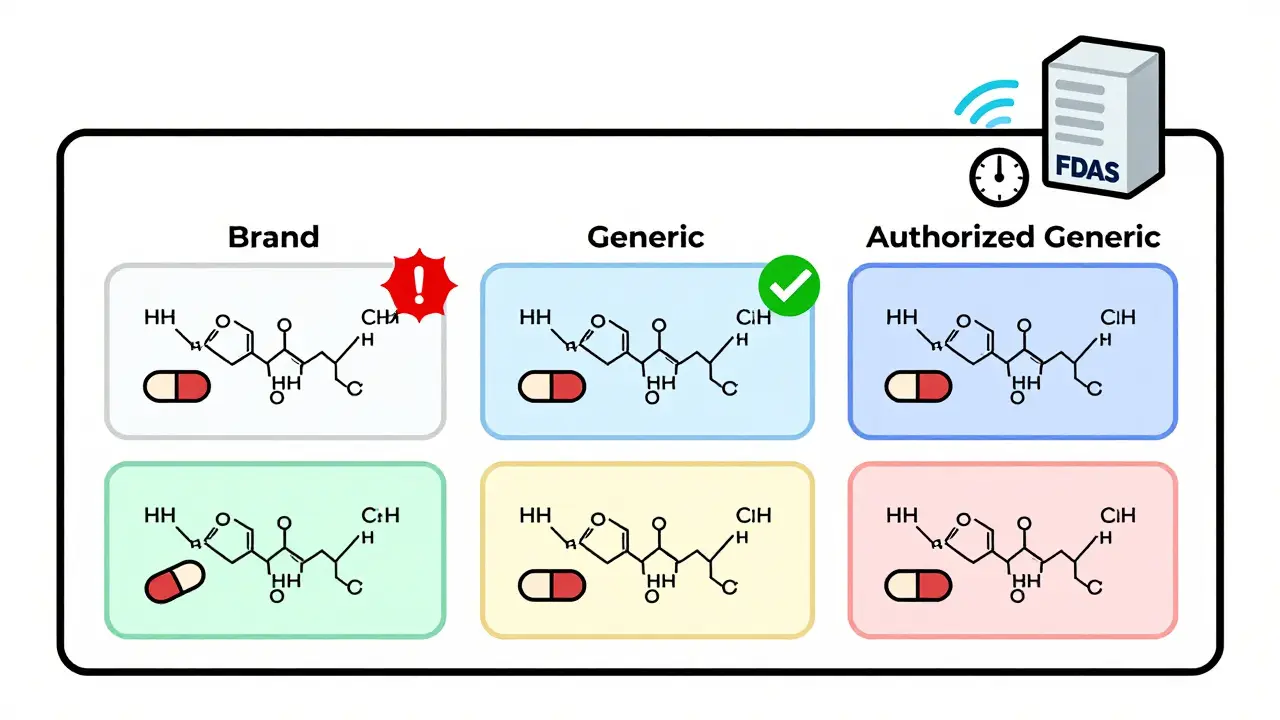

The FDA defines a generic drug as identical to its brand-name counterpart in dosage, strength, safety, and how it works. But here’s the catch: identical doesn’t mean identical in appearance. Generics look different. They have different names. They come from different manufacturers. And pharmacy systems have to sort through all of it-fast and accurately.

Think about lisinopril. There are over 17 different generic versions on the market. Some are made by the same company that makes the brand. Others are made by smaller labs. The system has to know which is which-not just for billing, but for safety. If a patient has had a bad reaction to a specific filler in one generic, the system should flag that. If a new generic just got approved, the system needs to update before it’s dispensed.

The National Drug Code (NDC) is the backbone of this system. Every drug-brand or generic-gets a unique 10- or 11-digit number. But here’s where it gets messy: the same drug can have multiple NDCs based on packaging size, manufacturer, or even distribution channel. A pharmacy system that doesn’t map these correctly will mix up prescriptions. And that’s not hypothetical. In 2022, a Walgreens pharmacist reported that their system flagged 17 different NDCs for lisinopril but didn’t tell them which ones were authorized generics-meaning the exact same drug as the brand, just sold under a different label.

The Orange Book: Your Secret Weapon

If you work in a pharmacy and you’re not using the FDA’s Orange Book, you’re flying blind. Officially called Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, this is the gold standard. It doesn’t just list drugs-it rates them. Each one gets a two-letter TE code. If it starts with an ‘A’, like AB or AO, it’s considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand. If it’s ‘B’, it’s not. Period.

Pharmacy systems like Epic, Cerner, and Rx30 pull this data directly. But here’s the problem: the Orange Book updates monthly. If your system only checks once a quarter, you’re working with outdated info. A new generic might have been approved last week, but your system still shows the brand as the only option. That means missed savings-and maybe even a patient getting a more expensive drug when they don’t need to.

Authorized generics are another layer. These are brand-name drugs sold under a generic label, made by the same company. They’re chemically identical to the brand. But pharmacy systems often treat them like any other generic. That’s misleading. A patient who switched from the brand to an authorized generic might think they’re getting a cheaper, lower-quality version-when in reality, it’s the exact same pill in a different box.

Branded Generics: The Confusion Multiplier

Ever heard of Errin, Jolivette, or Cryselle? They sound like brand names. They’re not. These are branded generics-drugs approved through the ANDA process but marketed under catchy names instead of chemical labels. They’re still generics. But patients and even pharmacists get tricked. A woman on birth control might be told, “We’re switching you to a cheaper option,” and assume she’s getting a generic. But if she’s switched from Errin to Jolivette, she’s still getting the same active ingredients. The system should know this. But too often, it doesn’t.

Pharmacy Times reported that 78% of pharmacists find it hard to distinguish between branded generics like Sprintec, Tri-Sprintec, and their generic equivalents. Why? Because the packaging, marketing, and even pill color differ across chains. A patient might get one version at CVS, another at Walgreens, and think they’re getting different drugs. The system needs to tie them all together under one therapeutic equivalence code. If it doesn’t, you’re creating confusion-and potential non-adherence.

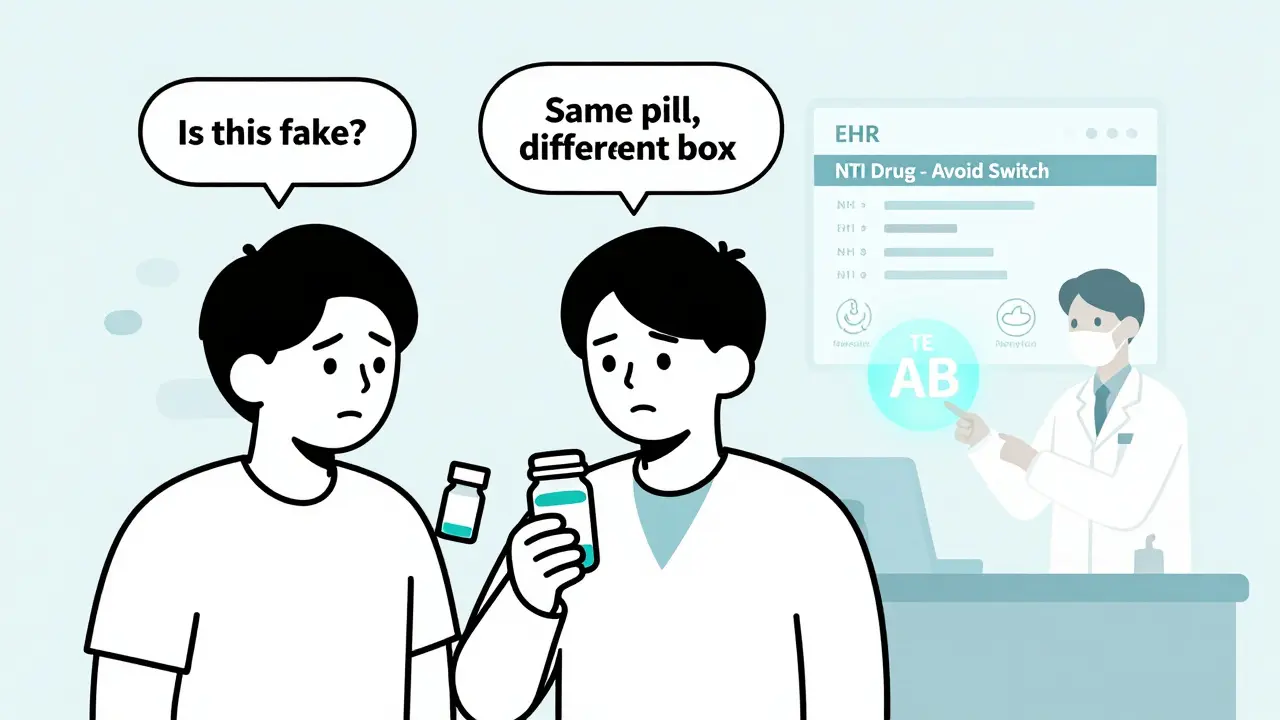

NTI Drugs: Where One Mistake Can Be Deadly

Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs are the most dangerous to mess up. These are medications where a tiny change in blood level can cause serious harm. Think warfarin, phenytoin, levothyroxine, and cyclosporine. For warfarin, a 5% difference in absorption can mean a clot or a bleed. For levothyroxine, even a 10% change can throw off thyroid levels for weeks.

GoodRx found that systems like Epic’s Beacon Oncology now have built-in alerts that block automatic substitution for NTI drugs. That’s good. But not all systems do. A 2021 ISMP report documented 147 adverse events over 18 months caused by inappropriate generic substitution of warfarin. Why? Because the system didn’t recognize the drug as NTI. Or the pharmacist didn’t see the alert. Or the patient didn’t know why they were switched.

Here’s the kicker: even if the generic is bioequivalent, some patients respond differently to different manufacturers. A 2019 study in U.S. Pharmacist found that 0.8% of patients on antiepileptic drugs had issues after switching-even though the generics met FDA standards. Why? Inactive ingredients. The filler, the coating, the dye. These don’t affect the drug’s action, but they can affect how it’s absorbed. And pharmacy systems? Most can’t track that.

What Best Practices Look Like in Real Pharmacies

Kaiser Permanente got this right. In 2022, they hit a 92.7% generic dispensing rate. How? Not by forcing it. By designing the system to default to generics-but with clear, smart exceptions.

- Prescribers can override the default if they want the brand.

- Patients get a simple handout explaining bioequivalence.

- The system shows side-by-side comparisons: brand name, generic name, cost difference, and therapeutic equivalence code.

Result? A 37% drop in patients asking to stay on brand-because they understood the switch was safe.

Humana’s system does something even smarter: it suggests therapeutic alternatives. If a doctor prescribes a brand, the system says: “This generic is equivalent and costs $12 less. Would you like to switch?” It doesn’t force it. It informs. And prescribers accept the suggestion 68% of the time.

Training matters too. ASHP recommends 8-10 hours of annual training for pharmacy staff on drug identification. Not just how to use the system-but what the codes mean, what authorized generics are, and how to explain it to patients. One pharmacist on Reddit said it best: “I had a patient cry because she thought her generic was ‘fake.’ She didn’t know it was made by the same company as the brand.”

State Laws and System Conflicts

California requires pharmacists to document why they didn’t substitute a generic. Texas lets them substitute without telling anyone. That’s a problem for systems that operate across state lines. A prescription filled in Texas might be processed by a system in Florida that expects documentation. The system crashes. Or worse-it auto-substitutes without the pharmacist knowing.

The FDA updates the NDC directory about 3,500 times a month. That’s over 100 changes per day. If your pharmacy system doesn’t auto-sync with the FDA’s API, you’re working with outdated data. And if you’re using an old system from 2018? You’re probably missing 40% of new generics approved since then.

What’s Next? AI, Genomics, and Real-Time Updates

The FDA’s 2023 Orange Book modernization is a game-changer. It’s moving to a machine-readable API that updates in real time-not monthly. That means pharmacy systems will know about new generics the same day they’re approved.

AI is stepping in too. A 2023 study in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association showed AI systems could predict potential equivalence issues with 87.3% accuracy by analyzing prescription patterns. For example, if a patient keeps switching between generics and has unstable INR levels, the system can flag it as a red flag-even if the TE code says it’s fine.

Long-term, pharmacogenomics might change everything. What if your genetic profile tells the system you respond better to one manufacturer’s levothyroxine? That data could be embedded in your EHR. The system wouldn’t just say “generic OK.” It would say, “Avoid this generic. Try this one.”

Bottom Line: It’s Not About Cost. It’s About Control.

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system nearly $2 trillion a decade. That’s huge. But the real win isn’t the savings. It’s giving patients safe, effective care without unnecessary expense. And that only happens when pharmacy systems get identification right.

Don’t just rely on defaults. Train your staff. Know your TE codes. Understand authorized generics. Use the Orange Book API. Explain the switch to patients. And never assume a generic is just a cheaper version of the brand-it’s not. It’s the same drug. And your system should treat it that way.

Are generic drugs really the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes, according to the FDA, generic drugs must have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also meet the same strict standards for quality, purity, and stability. The only differences allowed are in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) and appearance. Bioequivalence testing ensures they work the same way in the body. The FDA requires generics to deliver between 80% and 125% of the brand’s effect in the bloodstream-meaning they’re functionally identical.

What’s the difference between a generic and an authorized generic?

An authorized generic is made by the original brand-name manufacturer but sold under a generic label, usually at a lower price. It’s identical to the brand-same active ingredient, same factory, same formulation. The only difference is the packaging and name. Most pharmacy systems don’t distinguish between authorized generics and other generics, which can mislead patients into thinking they’re getting a lower-quality product. The FDA requires manufacturers to notify them when launching an authorized generic, but systems need to be updated to reflect this.

Why do some patients have problems switching from brand to generic?

While generics are bioequivalent, some patients report issues after switching-especially with narrow therapeutic index drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin. This isn’t because the generic is ineffective, but because small differences in inactive ingredients or manufacturing processes can affect how the drug is absorbed. A 2019 study found 0.8% of patients on antiepileptic drugs had adverse reactions after switching. These cases are rare, but they’re real. That’s why systems should flag NTI drugs and allow prescribers to override substitutions when needed.

How do pharmacy systems know which generics are equivalent?

They pull data from the FDA’s Orange Book, which assigns a Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) code to each drug. A code starting with ‘A’ (like AB, AO) means it’s equivalent to the brand. Systems like LexID and Medi-Span integrate this data directly into their databases. If a pharmacy uses a system that doesn’t sync with the Orange Book API, it may miss new generics or misclassify them. Best practice is to use systems that update daily and flag changes automatically.

Can pharmacists substitute generics without a doctor’s permission?

In 49 out of 50 states, pharmacists can substitute a generic for a brand-name drug if it’s rated therapeutically equivalent (TE code starting with ‘A’). The only exception is Delaware, which requires prescriber approval. However, even in states that allow substitution, pharmacists must follow state-specific rules. For example, California requires documentation of why a brand was kept. Some systems don’t account for this, leading to compliance risks. Always check your state’s pharmacy board rules.