Key Takeaways

- Dipyridamole works by raising platelet cAMP, which reduces clot formation.

- It is most often combined with aspirin for stroke prevention and used after heart surgery.

- Clopidogrel, aspirin, and warfarin are the most common alternatives, each with distinct mechanisms and risk profiles.

- Choosing the right agent depends on the clinical indication, patient comorbidities, and bleeding risk.

- Monitor for drug interactions, especially with anticoagulants and caffeine‑containing products.

When doctors need to keep blood from clotting, Dipyridamole is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor that raises cyclic AMP inside platelets, making them less sticky. It’s a niche antiplatelet that’s usually paired with aspirin or prescribed after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. But the market offers several other agents-some older, some newer-each with its own pros and cons. This guide walks through how dipyridamole stacks up against the most common alternatives, so you can see where it shines and where another drug might be a better fit.

How Dipyridamole Works

Dipyridamole blocks the re‑uptake of adenosine into red blood cells and endothelial cells, and it also inhibits phosphodiesterase‑5. The net effect is higher levels of cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP in platelets, which reduces platelet activation and aggregation. Unlike aspirin, which irreversibly acetylates COX‑1, dipyridamole’s effect is reversible and depends on the presence of the drug in the bloodstream.

Because its mechanism is indirect, dipyridamole is less likely to cause gastrointestinal bleeding than aspirin, but it can cause headache, dizziness, and a flushing reaction-often linked to its vasodilatory action.

Primary Clinical Uses

- Secondary stroke prevention: In the US, the FDA approved dipyridamole‑aspirin (Aggrenox) for patients who have already had an ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack.

- Post‑CABG antiplatelet therapy: Many cardiac surgeons prescribe dipyridamole for the first 30 days after graft surgery to keep the new vessels open.

- Peripheral arterial disease (PAD): Some clinicians add dipyridamole to improve walking distance, though evidence is mixed.

It is not a first‑line choice for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) because its onset is slower than clopidogrel or ticagrelor.

Alternatives at a Glance

Below are the most frequently considered substitutes. Each targets platelet function or the coagulation cascade differently.

- Clopidogrel: A thienopyridine that irreversibly blocks the P2Y12 ADP receptor on platelets.

- Aspirin: An irreversible COX‑1 inhibitor that reduces thromboxane A2 production.

- Warfarin: A vitamin K antagonist that interferes with clotting factor synthesis, acting on the coagulation cascade rather than platelets.

- Ticagrelor: A reversible P2Y12 inhibitor with a faster onset than clopidogrel.

- Heparin: An injectable anticoagulant that activates antithrombin to inhibit thrombin and factor Xa.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Feature | Dipyridamole | Clopidogrel | Aspirin | Warfarin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Phosphodiesterase inhibition → ↑cAMP/cGMP | P2Y12 ADP‑receptor blockade | COX‑1 inhibition → ↓thromboxane A2 | Vitamin K antagonist → ↓factor II, VII, IX, X |

| Onset of action | 2-4 hours | 5-7 days (requires metabolic activation) | 30‑60 minutes | 48‑72 hours |

| Typical dose | 75 mg 3 times daily (or 200 mg bid in combo) | 75 mg daily | 81‑325 mg daily | 2‑10 mg daily (INR‑guided) |

| Bleeding risk | Low‑moderate, mainly GI upset | Moderate, especially in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers | Higher GI bleed risk | High, requires INR monitoring |

| Key contraindications | Active bleeding, severe hypotension, recent surgery | Active bleeding, severe liver disease | Peptic ulcer disease, aspirin allergy | Pregnancy, uncontrolled hypertension |

| Monitoring needed? | No routine labs, watch for headache | Check platelet function in high‑risk patients | Consider GI prophylaxis | Frequent INR checks |

| Common drug interactions | Caffeine, NSAIDs, anticoagulants | PPIs (may reduce activation), CYP inhibitors | Anticoagulants increase bleed risk | Many: antibiotics, antifungals, vitamin K foods |

When Dipyridamole Is the Right Choice

Pick dipyridamole if you fall into one of these scenarios:

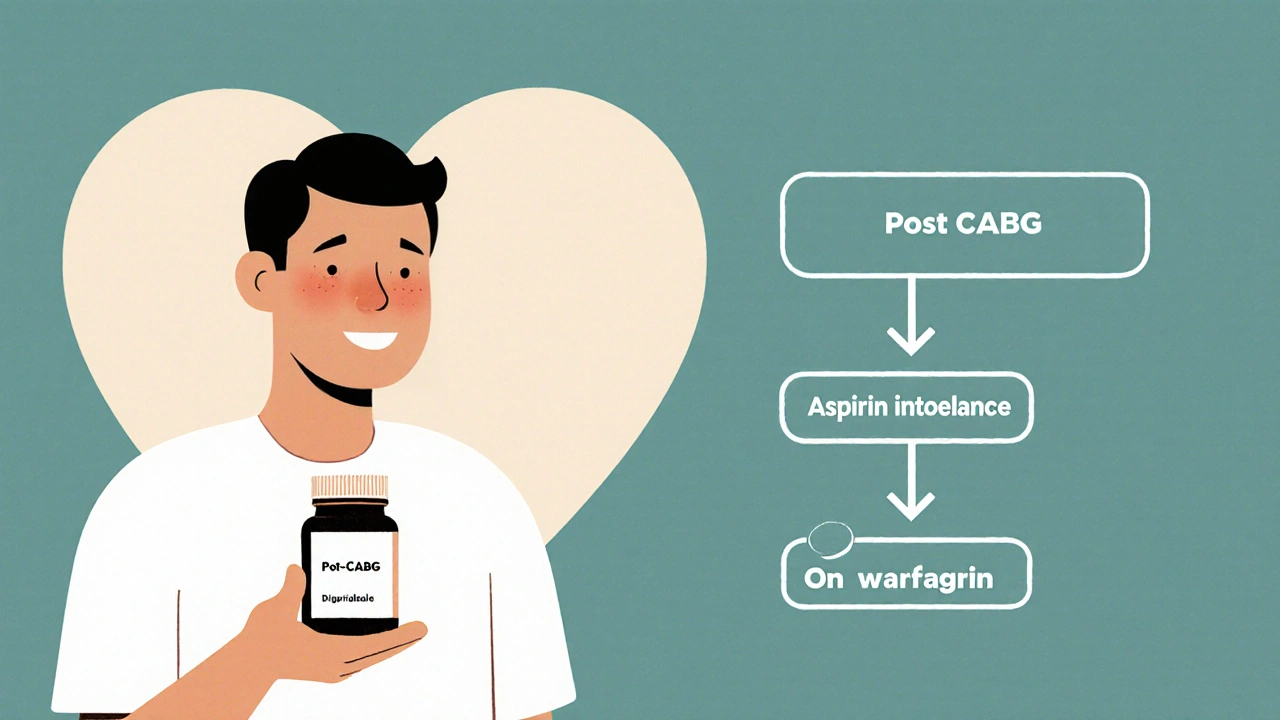

- Post‑CABG patients who need a mild antiplatelet effect without the higher bleed risk of aspirin‑only regimens.

- Patients with aspirin intolerance (e.g., severe gastric ulcer) who still need stroke prophylaxis-adding dipyridamole can fill the gap.

- Those on chronic anticoagulation (e.g., warfarin) where an extra platelet blocker is desired but excessive bleeding must be avoided.

In contrast, for acute coronary syndrome or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), a P2Y12 inhibitor like clopidogrel or ticagrelor is usually preferred because they act faster and have stronger evidence for preventing stent thrombosis.

Safety Profile and Common Side Effects

Most people tolerate dipyridamole well, but be on the lookout for:

- Headache and dizziness: Often related to vasodilation; can be mitigated by dose titration.

- Flushing-especially after the first few doses.

- GI upset-take with food to reduce nausea.

- Bleeding risk: While lower than aspirin, combining dipyridamole with other antithrombotics does raise bleed potential.

Unlike warfarin, dipyridamole does not require routine lab monitoring, which many patients appreciate.

Drug Interactions Worth Checking

Because dipyridamole raises adenosine levels, it can intensify the effects of other vasodilators. Common culprits include:

- Caffeine - may blunt the headache‑relieving effect.

- Non‑steroidal anti‑inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) - add GI bleeding risk.

- Anticoagulants (e.g., heparin, warfarin) - monitor for excess bleeding.

If you’re on a P2Y12 inhibitor, there’s usually no need to add dipyridamole unless a physician specifies a dual‑antiplatelet approach for a short period.

Practical Tips for Patients

- Take the dose exactly as prescribed; missing a dose can quickly reduce its protective effect.

- Swallow tablets whole with a full glass of water; crushing can increase side‑effects.

- Stay hydrated - dehydration may worsen headaches.

- Inform your pharmacist about any over‑the‑counter meds, especially caffeine‑rich supplements.

- Schedule regular check‑ins with your clinician if you’re on a combination regimen.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I replace aspirin with dipyridamole?

Dipyridamole works differently from aspirin. In many cases it’s added *to* aspirin, not swapped. If you’re allergic to aspirin, a doctor might prescribe dipyridamole‑only therapy, but the protective effect may be weaker for certain heart conditions.

How long should I stay on dipyridamole after heart surgery?

Typical protocols last 30 days post‑CABG, after which the doctor may switch you to aspirin alone or stop antiplatelet therapy altogether, depending on graft patency and overall risk.

Is dipyridamole safe during pregnancy?

Dipyridamole is classified as Pregnancy Category C. It should only be used if the potential benefit justifies the possible risk to the fetus, and always under close medical supervision.

What should I do if I get a severe headache?

Contact your healthcare provider. They may lower the dose, split it into smaller doses, or prescribe a short‑term analgesic. Never stop the medication abruptly without guidance.

Does dipyridamole interact with over‑the‑counter supplements?

Yes. High‑dose caffeine, ginkgo biloba, and some herbal vasodilators can amplify dipyridamole’s side‑effects. Always check with a pharmacist before adding new supplements.

By weighing the mechanism, onset, safety, and monitoring needs, you can decide whether dipyridamole or another antiplatelet/anticoagulant fits your health profile. Talk with your doctor about personal risk factors-such as prior bleed events, liver function, and concurrent meds-to land on the safest, most effective regimen.

13 Comments

Dipyridamole is just a glorified caffeine side‑effect filler.

While dipyridamole’s phosphodiesterase inhibition ↑cAMP and can mitigate thrombogenesis, its pharmacokinetic profile demands BID dosing 🕑 and consideration of adenosine‑mediated vasodilation 🌬️; the synergy with low‑dose aspirin remains evidence‑based in secondary stroke prophylaxis 🚑; however, clinicians must monitor for headaches, which are dose‑dependent and often manageable with titration. The drug’s half‑life approximates 6–8 h, necessitating adherence to maintain therapeutic plasma concentrations. Drug–drug interactions with NSAIDs and warfarin amplify bleed risk, so a thorough med‑review is non‑negotiable.

People love to hype dipyridamole like it’s some miracle, but the onset is lazy and the side‑effects feel like a cheap party‑drug hangover. If you can’t tolerate aspirin, you might as well look at clopidogrel instead of swapping for a “nice‑to‑have” vasodilator. Bottom line: it’s not the hero you think it is.

That’s a fair take - the slower onset can be a drawback when you need fast platelet inhibition.

For patients who can’t stomach aspirin, dipyridamole offers a gentler alternative while still providing stroke‑prevention benefits. 👍

In post‑CABG protocols, adding dipyridamole for the first month can help keep grafts patent without the higher GI bleed risk you see with full‑dose aspirin. It’s a balanced approach that many surgeons favor.

I hear you on the balance-keeping grafts open is critical and the lower bleed profile is a real plus for many patients.

Let’s unpack the drama surrounding dipyridamole. First, the molecule’s ability to boost cAMP and cGMP is scientifically elegant, yet clinicians often overlook how this translates to a subtle vasodilatory headache that can drive patients to the brink of frustration. Second, the drug’s interaction matrix is a labyrinth; combine it with NSAIDs and you’re courting a gastrointestinal catastrophe. Third, when paired with warfarin, the bleeding risk is not merely additive-it can become exponential, demanding meticulous INR surveillance. Fourth, the dosing schedule-three times daily-creates a compliance nightmare for anyone with a busy lifestyle. Fifth, the evidence for peripheral arterial disease benefits is mixed at best, leaving physicians to resort to anecdotal justification. Sixth, the FDA‑approved combo with aspirin (Aggrenox) is a clever marketing move, but it masks the fact that aspirin alone already provides substantial stroke protection for many. Seventh, the pharmacokinetics-half‑life of roughly 7 hours-means plasma levels dip dramatically if a dose is missed, eroding the protective effect. Eighth, the headache side‑effect, while often dismissed as “minor,” can precipitate a cascade of over‑the‑counter analgesic use, which in turn raises bleeding risk. Ninth, the lack of routine laboratory monitoring is a double‑edged sword: patients feel liberated, yet clinicians lose a safety net. Tenth, in the era of potent P2Y12 inhibitors like ticagrelor, dipyridamole feels like a relic, clinging to outdated guidelines. Eleventh, the drug’s cost, though modest, adds another pill to polypharmacy regimens, increasing the chance of accidental overdose. Twelfth, patient education is crucial-many are unaware that caffeine can blunt the therapeutic benefit, leading them to consume coffee indiscriminately. Thirteenth, the flushing phenomenon, while benign, can be socially embarrassing, affecting adherence. Fourteenth, the contraindication list-active bleeding, severe hypotension, recent surgery-covers a significant portion of the high‑risk population this drug is supposed to help. Fifteenth, the overall risk‑benefit calculus often tilts toward alternative agents with clearer efficacy data. In sum, dipyridamole is a niche player that demands careful patient selection, vigilant monitoring for side‑effects, and a realistic appraisal of its place in modern antiplatelet therapy.

Oh, sure, dipyridamole is the secret weapon hidden by a global pharma cabal that wants us all on their patented caffeine‑infused regimen. The “official” guidelines are just a veneer, while the real agenda is to keep us dependent on endless brand‑name pills. If you read between the lines, you’ll see that the “low‑bleed risk” claim conveniently ignores the covert micro‑vascular damage they never talk about. Anyway, enjoy your headache-it's probably the only thing keeping you awake enough to question the system.

Appreciate the perspective-you’re right that patients need clear guidance on how caffeine can blunt dipyridamole’s effect. In practice, we advise a moderate coffee intake (no more than 200 mg caffeine daily) and to take the medication with food to reduce GI irritation. Also, tracking headache severity on a simple 0‑10 scale can help clinicians adjust the dose before resorting to additional analgesics. By empowering patients with these practical steps, the therapeutic window can be optimized while minimizing side‑effects.

It is quite remarkable how the pharmaceutical industry manages to lobby for approval of agents like dipyridamole while simultaneously funding research that downplays its adverse profile. One must consider the hidden financial incentives that drive such approvals, especially when alternative agents with robust safety data exist. The regulatory narrative often masks an underlying strategy to expand market share under the guise of “combination therapy.”

From a pharmacological standpoint, dipyridamole’s reversible inhibition of phosphodiesterase distinguishes it from irreversible agents such as aspirin. Its pharmacodynamics require continuous plasma presence, necessitating strict adherence. Consequently, clinicians should assess patient reliability before prescribing.

Good overview, thank you.